The Great Books: Why They Matter and How to Teach Them

Walk into any classical school or homeschool co-op and you will find students reading books most adults have never touched. Homer. Plato. Augustine. Dante.

These are the Great Books, the foundational texts of Western civilization. They have shaped how people think, argue, worship, govern, and create for thousands of years. And they form the backbone of a classical Christian education.

But what exactly makes a book “great”?

Why do these ancient and medieval texts matter for students today?

And how do you actually teach them to a seventh grader or a high schooler who has never read anything more challenging than a young adult novel?

These are the questions we want to answer. The Great Books are more than a curriculum choice. They are an invitation into a conversation that has been going on for millennia, and your children can join the table.

What Are the Great Books?

The term “Great Books” refers to a collection of texts considered foundational to Western thought and culture. These include works of literature, philosophy, history, theology, science, and political theory. They span from the ancient world to the modern era, from Homer’s Iliad to Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov.

The Great Books Movement

The Great Books movement traces back to the 1920s, when Columbia professor John Erskine developed a seminar course built around reading primary texts.

The idea was rather revolutionary to modern educators at the time: rather than studying about great thinkers through textbooks and summaries, students would read the original works.

Robert Hutchins and Mortimer Adler later expanded this approach at the University of Chicago, eventually producing the famous Great Books of the Western World series in 1952.

What Makes a Book “Great”?

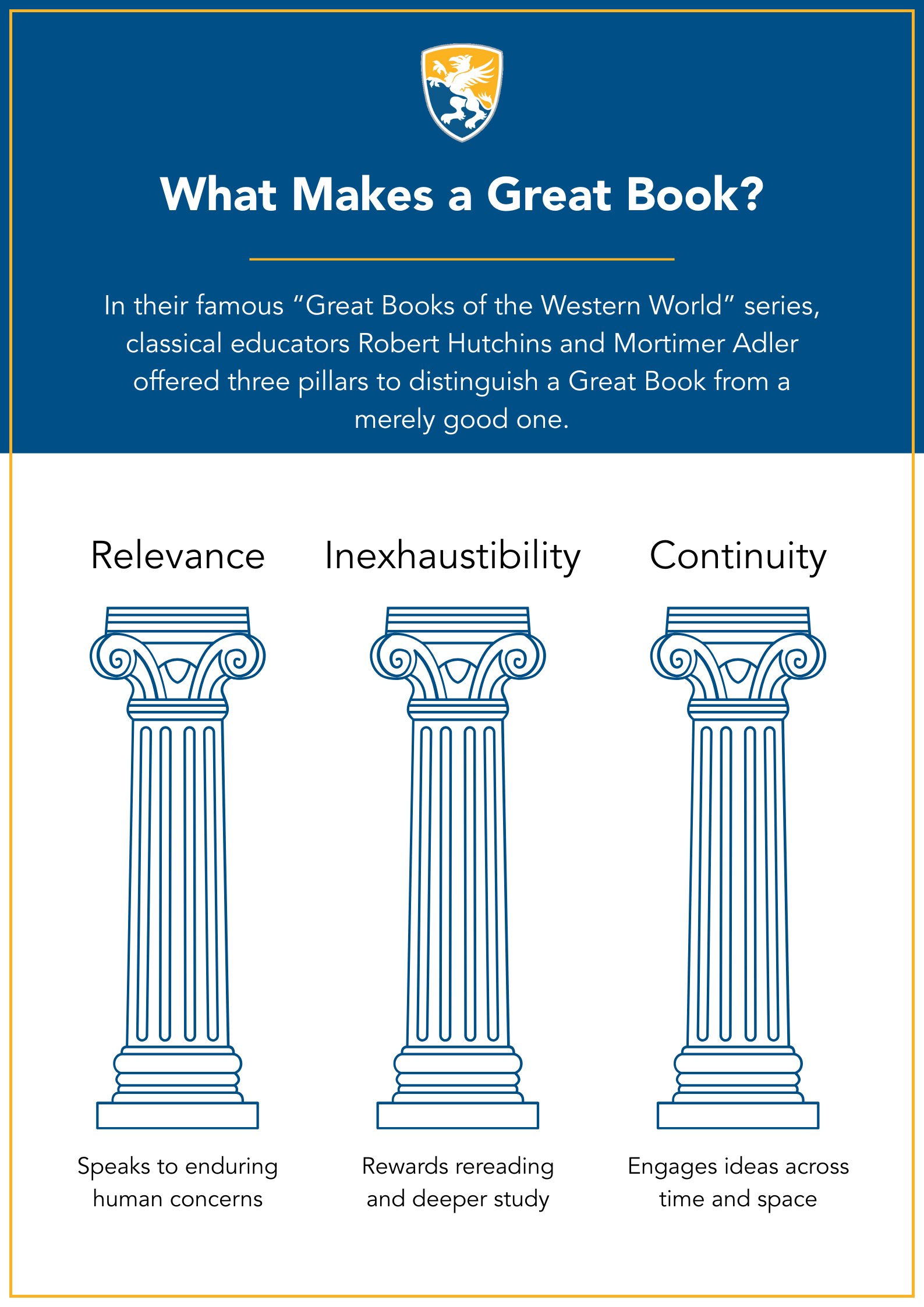

What distinguishes a Great Book from a merely good one? Hutchins and Adler had three criteria.

First, the book must be relevant, addressing important questions that still concern us today.

Second, the book must reward rereading and continued study.

Third, it must participate in what they called “the Great Conversation,” engaging with fundamental ideas that connect the greatest thinkers across time.

This last criterion is perhaps the most important.

The Great Books do not exist in isolation but respond to one another. Aristotle critiques Plato. Augustine wrestles with Cicero. Dante synthesizes classical philosophy with Christian theology. Milton reimagines Genesis. And so on.

Each generation of writers enters a dialogue with those who came before, agreeing, disagreeing, building, and refining. The Great Books are not a static canon to be memorized but a living conversation to be joined.

The Great Conversation

Hutchins put it this way: the tradition of the West is embodied in the Great Conversation that began in the dawn of history and continues to the present day. This conversation covers the deepest questions humans have ever asked.

What is justice? What is beauty? What is the good life? What do we owe to one another? What happens after death? What is the nature of God?

Questions That Have Never Been Settled

These questions have never been settled. That is why the conversation continues. Plato answered the question of justice one way in the Republic. Aristotle offered a different answer in his Nicomachean Ethics. Thomas Aquinas synthesized their insights with Christian revelation. John Locke challenged that synthesis with a new theory of natural rights.

And the conversation goes on and into our own time.

Entering the Conversation

When students read the Great Books, they are not simply absorbing information about what historical people thought. They are entering this conversation. They begin to see how ideas have consequences, how one generation’s answers become the next generation’s questions. They learn that thoughtful people have disagreed about fundamental matters, and they are challenged to think through these questions for themselves.

This is what distinguishes classical education from mere transmission of facts. We are teaching students to think carefully about questions that matter, to weigh competing arguments, to recognize the strengths and weaknesses of different positions, and ultimately to take their own place in the ongoing conversation of Western civilization.

The Canon: A Reading List or Something More?

The word “canon” comes from the Greek word for “rule” or “measuring rod.”

In its literary sense, it refers to a body of works considered authoritative. The Western canon, then, is the collection of texts that have been recognized as foundational to Western thought.

Different scholars have proposed different lists. Harold Bloom’s The Western Canon places Shakespeare at the center, surrounded by Dante, Chaucer, Cervantes, Milton, Tolstoy, and others, while Mortimer Adler’s Great Books of the Western World included works from Homer through Freud. Various university programs have developed their own reading lists.

But the canon is more than a reading list. It represents a shared inheritance, a common vocabulary of stories, ideas, arguments, and images that educated people have drawn upon for centuries. When someone alludes to Achilles’ wrath or Odysseus’ journey home, when they invoke Plato’s cave or Augustine’s restless heart, they are drawing on this shared inheritance. The canon creates a common culture of discourse.

A Christian Perspective on the Great Books

For Christians, the Great Books raise an obvious question: why should we spend time reading pagan philosophers and secular authors when we have the Scriptures? The answer lies in understanding both the limits and the value of human wisdom.

Common Grace and Fragments of Truth

The ancients got many things wrong. They worshiped false gods. They justified slavery. They built philosophies on foundations that could not bear the weight.

And yet, by God’s common grace, they also glimpsed fragments of truth. The Greeks asked what virtue was and recognized that human beings long for something beyond themselves. The Romans developed sophisticated thinking about law, justice, and the common good. The philosophers sought wisdom with an earnestness that puts many modern thinkers to shame.

Christ as Fulfillment

Into this world came Christ, the fulfillment of all that the ancients longed for. Augustine didn’t reject Plato. He adopted him, showing how the best of classical philosophy pointed toward the God revealed in Scripture. The early church fathers engaged the great thinkers of their day, recognizing truth wherever they found it while anchoring everything in biblical revelation.

Reading with Discernment

A classical Christian education follows this pattern.

We do not read the pagan classics (ancient or modern) blindly, accepting everything they say. But neither do we dismiss them as worthless. We read them charitably, looking for what is true, good, and beautiful, while measuring everything against the standard of Scripture.

Students learn to appreciate the insights of great thinkers while also seeing where they fall short. They see how the deepest questions of human existence point toward the Gospel. And they develop the discernment to engage any text, ancient or modern, with both intellectual honesty and theological confidence.

What Makes a Classical Literature Curriculum Different

A classical approach to literature differs fundamentally from the approach taken in most contemporary schools.

In a modern curriculum, literature is often organized thematically or by genre. Students might spend a unit on “coming of age” stories, reading selections from different time periods grouped around a common theme. Or they might study “the short story” as a form, reading examples from various authors without attention to historical context.

Chronological and Integrated

A classical curriculum takes a different approach. Literature is studied chronologically, alongside the history of the period in which it was written.

Students read Homer while studying ancient Greece. They read Virgil while studying Rome. They read Beowulf and Dante while studying the medieval world.

This integration allows students to understand how literature both reflects and shapes its historical moment. They see how ideas develop over time, how writers respond to their predecessors, how the Great Conversation unfolds across centuries.

Primary Sources Over Summaries

A classical curriculum also emphasizes primary sources over textbooks and summaries. So, rather than reading about Plato, students read Plato himself. And rather than studying a chapter on the Reformation, they might read Luther’s writings.

This direct encounter with primary texts is challenging, but it is also far more rewarding. Students learn to grapple with difficult ideas in the author’s own words. They develop the skills to read carefully, to ask questions, to trace arguments, and to form their own judgments.

The Trivium and the Great Books

Classical education follows the natural development of a child’s mind through three stages: grammar, logic, and rhetoric. Each stage shapes how students engage with great texts.

This is called the trivium.

The Grammar Stage

In the grammar stage (roughly grades K through 6), children excel at absorbing information. Their minds are wired for memorization. They delight in songs, chants, and stories. At this stage, students are not yet ready for the Great Books themselves, but they are preparing for them. They learn the basic facts of history, the timeline of Western civilization, the stories of the Bible. They memorize poetry and Scripture. They build the foundation of knowledge that will support deeper study later.

The Logic Stage

In the logic stage (roughly grades 7 through 9), students begin to ask “why.” They want to understand how things connect, to find the reasons behind the facts. This is when students are ready to begin reading the Great Books, though at a level appropriate to their development. They learn to follow arguments, identify assumptions, and spot logical fallacies. They read primary sources and ask questions: Why did Homer portray Achilles this way? What is Plato really arguing in the Republic? How does Augustine’s view of human nature differ from Aristotle’s?

The Rhetoric Stage

In the rhetoric stage (roughly grades 10 through 12), students learn to express their own ideas with clarity and persuasion. They have accumulated knowledge. They have learned to think logically. Now they must learn to communicate effectively. They engage the Great Books at a deeper level, writing essays that interact with the texts, participating in debates, and articulating their own positions on the great questions. The goal is not merely to understand what others have thought but to join the conversation themselves.

Different Ages, Different Encounters

This progression means that students encounter the Great Books differently at different ages.

A seventh grader reading Herodotus focuses on following the narrative and understanding the basic arguments. A tenth grader reading Herodotus asks harder questions about methodology, bias, and historical reliability.

Both encounters are valuable. Both are appropriate to the student’s stage of development.

The Socratic Method: Learning Through Questions

One of the most powerful tools for teaching the Great Books is the Socratic method, named after the ancient Athenian philosopher who appears throughout Plato’s dialogues. Socrates did not lecture. He asked questions. Through careful, probing inquiry, he led his students to examine their assumptions, clarify their thinking, and discover truth for themselves.

Active Participation

The Socratic method works because it treats students as active participants rather than passive recipients. Instead of telling students what a text means, the teacher asks:

What do you think Plato is arguing here? Why might someone disagree? What evidence supports your interpretation?

This approach requires students to think, to engage, to take ownership of their learning.

In a Socratic discussion, there is no hiding. Students cannot simply sit back and absorb information. They must read carefully, formulate their own views, and be prepared to defend them. They learn that their opinions must be grounded in the text, that assertions require evidence, that other perspectives deserve consideration. These habits of mind serve them long after the discussion ends.

Intellectual Humility

The Socratic method also models intellectual humility.

Socrates famously claimed that he knew nothing, that his wisdom consisted in recognizing his own ignorance. A good Socratic discussion is not about the teacher proving how much he knows. It is about the community of learners pursuing truth together. Students discover that even the teacher does not have all the answers, that some questions remain genuinely open, that the pursuit of wisdom is a lifelong endeavor.

Our Approach: Omnibus

At Veritas Press, our Great Books program is called Omnibus, a Latin term meaning “all-encompassing.” The name fits. Omnibus integrates history, theology, and literature into a unified course of study. Rather than treating these disciplines as separate subjects, Omnibus shows students how they connect: how ideas in philosophy shaped political events, how historical circumstances influenced literary works, how theological convictions permeated every aspect of a culture.

Six Years, Three Historical Periods

The Omnibus curriculum spans six years, from seventh grade through twelfth grade. It cycles through three historical periods: Ancient (biblical and classical civilizations), Medieval (the church fathers through the Reformation), and Modern (the Reformation to the present).

Students complete this cycle twice, once at the logic stage and once at the rhetoric stage, encountering the same historical periods with increasing depth and sophistication.

Primary and Secondary Courses

Each year includes two simultaneous courses: Primary and Secondary.

The Primary course focuses on primary-source historical works and the great classical texts. Students read Herodotus, Plato, Augustine, Dante, Shakespeare, and many others.

The Secondary course provides balance with a greater focus on literature and theology, including works by C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and other significant Christian authors.

Taken together, students earn three credits each year: one in history, one in theology, and one in literature.

Integration and Scripture

What makes Omnibus distinctive is its integration.

Students do not simply read great books in isolation. They study them alongside the historical events and theological debates of their time. They see how Plato’s philosophy influenced Christian thought. They understand why the Reformation produced such profound changes in literature and politics. They trace the development of ideas across centuries, watching the Great Conversation unfold.

Over the six years of Omnibus, students will have carefully studied every book of the Bible. This is intentional. Scripture is the ultimate standard against which all other texts are measured. The Great Books illuminate the human condition, but only the Bible reveals the divine remedy. By reading the classics alongside Scripture, students learn to think biblically about everything.

Can My Child Really Do This?

This is the question every parent asks. Can a seventh grader really read Herodotus? Can a high schooler engage with Plato’s Republic? The reading lists look daunting. The texts are challenging. It is natural to wonder if your child is ready.

Students Are More Capable Than We Think

The answer is yes, with some important qualifications. Students who have been receiving a classical education in the grammar years are well prepared for this work. They have built a foundation of knowledge, memorized timelines and facts, developed vocabulary and reading skills. The logic and rhetoric stages build on this foundation.

Even students who are new to classical education can succeed, though they may need additional support at first. The Omnibus curriculum is designed with this in mind. The readings are carefully selected to fit the stage of the learner. Students are encouraged to skim some sections (Herodotus’s Histories, for instance, rewards selective reading) and to savor others (Homer’s Odyssey deserves slow attention).

The goal is not to master every detail but to engage with the great ideas, to begin thinking about the questions that have occupied the wisest minds in history.

A Bridge for Younger Students

For students who need a bridge to the more rigorous Omnibus courses, we offer a History Transition Guide designed to prepare younger students for a Great Books-based program. This course helps students become familiar with the chronological approach and the kind of reading they will encounter in Omnibus.

Three Ways to Study the Great Books

Families are different. Some parents want to teach these texts themselves. Others want their students to work independently. Still others want the accountability and interaction of a live classroom. We have built Omnibus to accommodate all three approaches.

You-Teach puts parents in the driver’s seat. You receive the complete curriculum materials, including the student text, teacher resources, and reading lists. You lead the discussions, grade the assignments, and guide your student through the Great Books. This option works well for parents who love teaching, who want to learn alongside their children, or who have strong convictions about being directly involved in instruction.

Self-Paced offers flexibility and independence. Students work through the material on their own schedule, interacting with video lessons taught by experienced Omnibus instructors. The courses include engaging teaching filmed at historical sites throughout Europe, bringing the material to life. This option works well for self-motivated students, families with irregular schedules, or parents who want rigorous content without daily teaching demands.

Live online courses through Veritas Scholars Academy provide instruction. Students join real-time classes with a Veritas teacher and other classical students from around the world. They participate in Socratic discussions, receive feedback on their writing, and experience the community of learning that comes from studying great texts together. This option works well for students who thrive with external structure, families who want expert instruction in challenging subjects, or parents looking for the accountability of a traditional classroom.

Any study of the Great Books will be of great value. Whether you plan to complete all twelve Omnibus courses over six years or only one or two, students will benefit for the rest of their lives by joining the Great Conversation.

The Goal: Students Who Can Think

The Great Books are not an end in themselves.

We do not read Homer and Plato simply to say we have read them. We read them because of what they do to us. They expand our imagination. They sharpen our thinking. They humble us with the recognition that brilliant people have wrestled with hard questions for millennia. And they equip us to develop our own voice with wisdom and conviction.

A student who has read the Great Books knows that ideas matter. They have seen how philosophical assumptions shape civilizations, how theological commitments produce revolutions, how a single book can change the course of history. They are not easily swayed by the latest trends or the loudest voices because they have encountered the deepest thinkers.

A student who has read the Great Books can articulate and defend what they believe. They have practiced making arguments, analyzing positions, and responding to objections. They know how to read carefully, write clearly, and speak persuasively. These are skills that serve them in college, in their careers, and in every conversation that matters.

A student who has read the Great Books from a Christian perspective understands that all truth is God’s truth. They can appreciate the insights of pagan philosophers while recognizing their limitations. They see how the longings expressed in ancient literature find their fulfillment in Christ. They are prepared to engage the world not with fear but with confidence, knowing that the Christian faith has nothing to hide from honest inquiry.

This is what we mean when we say we are preparing students for life. The Great Books are not a detour from practical education. They are the most practical education we can offer: the formation of minds that can think, hearts that can love what is good, and souls that are anchored in truth. We would love for your family to join us in this work.