What Is the Socratic Method? (And Why the Best Classrooms Still Use It)

What if the best way to teach wasn’t to give answers but to ask questions?

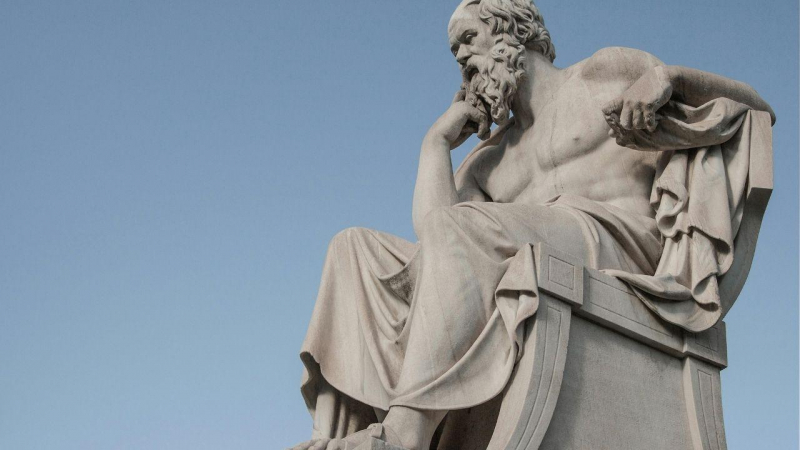

Twenty-four centuries ago, a philosopher wandered the streets and marketplaces of Athens engaging anyone who would listen in conversation. He didn’t lecture. He didn’t hand out scrolls of information to memorize. Instead, he asked questions. Probing, persistent, sometimes uncomfortable questions that forced people to examine what they actually believed and why.

His name was Socrates. His method was so powerful that it’s still used today in the world’s best classrooms, law schools, and boardrooms.

And it was so disruptive that the Athenians eventually executed him for it.

This guide will walk you through the Socratic method. We’ll talk about the method’s origins, how it works in classical classrooms, and how you can use it at home with your own children. Whether you’re new to classical education or already part of the Veritas community, understanding the Socratic method will deepen your appreciation for what makes this approach to learning so powerful. And it produces something that conventional education often misses: students who can think for themselves.

What Is the Socratic Method?

The Socratic method is a form of teaching and inquiry based on asking and answering questions. Rather than lecturing or simply providing information, the teacher guides the student toward understanding through dialogue. The goal is to help students discover truth for themselves.

Named after the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates (470–399 BC), this approach emphasizes how to think rather than what to think. Through careful questioning, the teacher exposes assumptions, clarifies concepts, and tests the consistency of beliefs. The student doesn’t passively receive information. They actively construct understanding.

This is why the Socratic method sits at the heart of classical education. Classical learning aims to form students who can learn anything, think carefully, and engage wisely with the world.

The Socratic method is one of the primary tools for accomplishing that goal.

The Core Principle: Questions Over Answers

Socrates believed that true knowledge couldn’t simply be handed from one person to another. Knowledge has to be discovered. Telling someone an answer is far less powerful than guiding them to find it themselves.

He compared his role to that of a midwife. His mother, Phaenarete, was a midwife who helped bring babies into the world. Socrates saw himself as an intellectual midwife, someone who helped give birth to ideas already latent in the student’s mind.

The knowledge was there but needed to be drawn out.

This is why Socratic teaching feels different from conventional instruction. In a lecture, the teacher is the active party and the student is passive, receiving information. In Socratic dialogue, the student is active, wrestling with questions, testing ideas, and arriving at understanding through their own reasoning. The learning sticks because the student has done the work.

For parents, this distinction matters.

You’ve probably watched your child memorize facts for a test, only to forget them a week later. Socratic learning produces something different: understanding that lasts because the student has earned it through their own thinking.

Socratic Irony and Intellectual Humility

Socrates famously claimed that “I neither know nor think I know.” When the Oracle at Delphi declared him the wisest man in Athens, he was baffled. He set out to find someone wiser and discovered that the Oracle was right, but not in the way he expected. Others claimed to know things they didn’t actually understand. Socrates, at least, knew that he didn’t know.

This “Socratic irony” was a stance of intellectual humility that created space for genuine inquiry. If you already have all the answers, why would you ask questions? But if you recognize the limits of your understanding, you become open to learning.

Classical education prizes this intellectual humility. We want students who are confident in their convictions but humble enough to keep learning. The Socratic method models this posture. Students learn that wisdom begins with recognizing what they don’t know, and that this recognition is the first step toward genuine knowledge.

A Brief History: From Ancient Athens to Classical Education Today

The Socratic method isn’t a modern educational technique or a trendy pedagogical innovation. Rather, it’s been tested and refined over more than two thousand years, preserved and transmitted through the classical tradition.

Socrates and the Agora

Socrates lived in Athens during its golden age, the era of Pericles, the Parthenon, and the birth of democracy. He didn’t teach in a school or charge fees. He simply talked to people.

In the agora (the public marketplace), in the gymnasiums, wherever his fellow Athenians gathered, Socrates engaged them in conversation. He questioned politicians about justice, generals about courage, poets about beauty. No one was too important or too ordinary for dialogue.

Socrates left no writings. Everything we know about his method comes from his students, especially Plato, whose dialogues capture Socratic questioning in action. In works like the Meno, the Euthyphro, and the Republic, we watch Socrates guide his interrogators through complex questions (What is virtue? What is piety? What is justice?) using nothing but careful questioning.

His method was so effective, and so unsettling to those in power, that he was eventually put on trial. The charge: corrupting the youth and impiety toward the gods. The real offense: teaching young people to question everything, including the assumptions of their elders. Socrates was convicted and executed in 399 BC, choosing to drink hemlock rather than abandon his principles.

The Classical Tradition Preserves the Method

Socrates’ death didn’t end his influence. Plato founded the Academy, which endured for centuries. Aristotle, Plato’s student, continued the tradition of dialectical inquiry. The Socratic method became embedded in classical education.

Medieval scholars adapted the approach into disputatio, structured debates where students defended and attacked philosophical and theological propositions. The great universities of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna trained generations of thinkers through this Socratic-inspired method. Later, Renaissance humanists rediscovered the Platonic dialogues and revived interest in Socratic education.

The thread runs unbroken from ancient Athens to the classical education revival happening today. When a student participates in a Socratic discussion at Veritas Scholars Academy, for example, they’re part of a tradition stretching back more than two millennia, discovering and returning to truth, knowing what they believe and why.

Why Classical Education and the Socratic Method Belong Together

The Socratic method has found applications in many fields. Law schools use it to train attorneys to think on their feet. Therapists use Socratic questioning to help patients examine their thoughts. Business coaches use it to develop leaders.

But the Socratic method finds its fullest expression in classical education, because classical education shares its fundamental goal: forming minds that can think.

Classical education follows the natural development of the mind through the stages of the trivium. In the grammar stage, young children excel at absorbing information. In the logic stage, they learn to ask “why” and reason carefully. In the rhetoric stage, they learn to articulate and defend their own ideas persuasively.

The Socratic method aligns perfectly with this progression. As students mature into the logic and rhetoric stages, Socratic dialogue becomes the primary mode of instruction. They don’t just learn facts about history, literature, or philosophy. They engage with primary sources, wrestle with ideas, and develop their own reasoned positions through discussion and debate.

How the Socratic Method Works: The Art of Questioning

That’s all well and good, but here’s the big question: What does Socratic teaching actually look like in a classical classroom or around your dinner table?

The Structure of Socratic Dialogue

A Socratic dialogue typically follows a recognizable pattern:

1. It begins with a question. Often the question seems simple, deceptively so.

- “What is courage?”

- “What makes something beautiful?”

- “Is it ever right to lie?”

The simplicity is the trap. Everyone thinks they know the answer until they try to articulate it.

2. The student offers an answer. They propose a definition, state an opinion, or make a claim. This is their starting point, what they think they know.

3. The teacher asks follow-up questions. Not to argue, but to probe.

- “Can you give me an example?”

- “Does that definition cover all cases?”

- “What about this situation? Would your definition apply?”

The goal is to test the answer, to see if it holds up under examination.

4. Contradictions or gaps emerge. The student realizes their initial answer was incomplete, inconsistent, or wrong. This moment of recognition, what the Greeks called aporia (puzzlement), is uncomfortable but essential. It creates the opening for genuine learning.

5. The student refines their thinking. With the teacher’s guidance, they develop a better answer, one that accounts for the problems they’ve discovered. But that answer, too, may be questioned.

6. The cycle continues. Each refined answer faces new questions, spiraling toward deeper understanding. The dialogue may not reach a final, definitive answer, but the student’s thinking has been transformed in the process, and they now have greater clarity around what they believe and why

Types of Socratic Questions

Not all questions are Socratic. What distinguishes Socratic questioning is its purposefulness. Each question is designed to advance understanding, not just to check facts or fill silence.

There are six main categories of Socratic questions:

1. Clarifying questions ensure the teacher understands what the student means, and that the student understands their own meaning.

- “What do you mean by ‘fair’?”

- “Can you put that another way?”

- “Can you give me an example of what you’re describing?”

2. Questions that probe assumptions uncover the beliefs underlying the student’s position.

- “What are you assuming when you say that?”

- “Why do you think that’s true?”

- “What would have to be true for your answer to be correct?”

3. Questions that probe reasons and evidence examine the foundation of the student’s claims.

- “How do you know that?”

- “What evidence supports your view?”

- “What led you to that conclusion?”

4. Questions about implications and consequences explore where the student’s reasoning leads.

- “If that’s true, what follows?”

- “What would be the consequences of that?”

- “How does that affect your original claim?”

5. Questions that examine viewpoints and perspectives broaden the student’s thinking.

- “How would someone who disagrees with you respond?”

- “What’s another way to look at this?”

- “Why might a reasonable person reach a different conclusion?”

6. Questions about the question itself develop metacognitive awareness.

- “Why do you think I asked that question?”

- “Why does this question matter?”

- “What makes this a difficult question?”

A skilled Socratic teacher moves fluidly among these types, responding to what the student actually says rather than following a script. This is why Socratic teaching is an art that develops with practice.

The Role of the Teacher

In Socratic dialogue, the teacher’s job is fundamentally different from conventional instruction. They’re not dispensing information. They’re guiding discovery.

This requires deep listening. The teacher must pay close attention to the student’s actual reasoning, not just waiting for their turn to speak, but genuinely engaging with what the student is thinking. The next question depends on understanding this answer.

It also requires restraint. The temptation to simply give the answer is constant, especially when you can see exactly where the student is going wrong. But the Socratic teacher resists. They know that an answer given is less valuable than an answer discovered.

The teacher creates a safe space for intellectual risk-taking. Students must feel free to venture ideas, make mistakes, and be corrected without humiliation. The goal is growth, not gotcha moments.

Finally, the teacher models the very virtues they’re trying to develop: curiosity, humility, careful reasoning, respect for evidence. They demonstrate what it looks like to take ideas seriously.

The Socratic teacher know that an answer given is less valuable than an answer discovered.

The Role of the Student

Socratic learning demands more from students than sitting quietly and taking notes. Students must participate actively, offering ideas, responding to questions, building on what others have said.

This requires intellectual courage. It’s risky to voice an idea that might be shown to be wrong. But that risk is where learning happens. Students learn that being wrong isn’t shameful. It’s an opportunity to think more carefully.

It also requires intellectual humility. Students must be willing to change their minds when the evidence and reasoning warrant it. They learn to hold their beliefs with appropriate tentativeness, confident enough to state them but open enough to revise them.

Over time, students internalize the questioning process itself. They begin to ask themselves the questions the teacher has been asking. They become, in a sense, their own Socratic questioners. This is one of the great gifts of classical education: students who can continue learning on their own because they’ve learned how to examine their own thinking.

The Socratic Method in Classical Education

How does Socratic teaching work in actual classical schools, with actual children? And what does it produce?

The Trivium and Socratic Learning

Classical education follows the Trivium, three stages that align with a child’s natural cognitive development. The Socratic method plays a different role at each stage.

In the grammar stage (roughly elementary school), children excel at memorization and absorption. They learn facts, vocabulary, timelines, and rules. Socratic dialogue plays a supporting role here, with simple questions helping children explore what they’re learning. “Why do you think the colonists were upset about taxation?” “What do you notice about this poem?”

In the logic stage (roughly middle school), children become naturally more argumentative. They want to know why. They spot inconsistencies and challenge explanations. Classical education leans into this tendency rather than suppressing it. Socratic dialogue becomes more central as students learn to construct and evaluate arguments. They examine causes and effects, compare perspectives, and identify logical fallacies.

In the rhetoric stage (roughly high school), students are ready for the full expression of Socratic learning. They engage with primary sources, the Great Books of Western civilization, through discussion and debate. They don’t just analyze others’ arguments. They develop and defend their own. A Veritas Omnibus class, for instance, might spend an hour discussing whether Achilles was heroic or selfish, with students drawing on the text of Homer to support their positions.

What Classical Students Gain

Students who experience Socratic learning through a classical education develop capabilities that serve them for life.

They learn to think critically. They can analyze arguments, evaluate evidence, and construct sound reasoning. They recognize logical fallacies in others’ arguments and their own. In a world saturated with information and persuasion, this ability to think carefully is invaluable.

They learn to communicate clearly. Socratic dialogue requires students to formulate and express their ideas precisely. They practice listening carefully, responding thoughtfully, and building on others’ contributions. These skills translate directly into better writing, better speaking, and better conversation.

They develop intellectual humility. They learn that it’s okay to not know, and valuable to find out. They hold their views with appropriate confidence: firm enough to state them clearly, open enough to revise them when warranted.

They understand deeply rather than superficially. Information learned through active questioning is retained longer and understood more thoroughly. Students grasp underlying principles, not just surface facts. They can apply their knowledge to new situations because they understand the why behind the what.

They’re prepared for college and beyond. College seminars, especially in the humanities and in graduate programs, use Socratic methods. Students who’ve experienced this kind of learning arrive prepared to participate and lead. But the benefits extend beyond academics. Leadership, parenting, citizenship, professional life: all reward the skills that Socratic classical education develops.

What Socratic Teaching Looks Like at Veritas Scholars Academy

At Veritas Scholars Academy, Socratic dialogue is woven into the curriculum, especially in the Omnibus courses, our signature Great Books program.

In an Omnibus class, students don’t just read the classics. They discuss them. A teacher might open a session on Plato’s Republic by asking: “Is Socrates right that it’s always better to suffer injustice than to commit it?” Students take positions, offer reasons, and respond to challenges. The teacher asks follow-up questions. Students refine their views.

The discussion might range across the text, bringing in other works, considering counterarguments, exploring implications. By the end, students understand Plato because they’ve thought about him themselves, out loud, in community, with guidance from a teacher who knows the text deeply.

Our teachers are trained in Socratic facilitation. They know how to ask the right questions, when to push further, and how to create an environment where students feel safe taking intellectual risks. Live, interactive classes make real dialogue possible, even online.

This is what rigorous classical education looks like. It’s demanding, but it’s also deeply engaging. Students who experience this kind of learning often find that they don’t want to go back to passive absorption.

Using Socratic Questions at Home

You don’t need a philosophy degree to use Socratic questioning with your children. With a few simple techniques, you can turn everyday conversations into opportunities for deeper thinking.

Start with Genuine Curiosity

The Socratic approach works best when it comes from genuine interest, not interrogation. You’re not trying to trap your child or prove them wrong. You’re trying to understand how they think and help them think more carefully.

Ask questions because you’re genuinely curious about their reasoning. What makes them think that? How did they reach that conclusion? What would change their mind?

Be patient. Give them time to think before answering. Resist the urge to fill the silence or answer your own questions. Some of the best learning happens in those uncomfortable pauses.

Practical Questions to Try

When your child states an opinion:

- “That’s interesting. Why do you think that?”

- “How would you explain that to someone who disagreed?”

- “What’s the strongest argument against your view?”

When reading a book together:

- “Why do you think the character did that?”

- “Was that the right decision? Why or why not?”

- “What would you have done differently?”

When studying history or current events:

- “What do you think caused that to happen?”

- “Were the people involved right or wrong? How do you decide?”

- “What might someone on the other side have said?”

When discussing a moral question:

- “What makes that right or wrong?”

- “Is there ever an exception to that rule? When?”

- “How do you know?”

These questions work for children of all ages. You simply adjust the complexity of the topics and the depth of the follow-up.

Tips for Effective Socratic Conversations

Don’t answer your own questions. Wait, even if the silence stretches on. Your child needs the space to think.

Follow up on their answers. One question is a quiz. A series of questions is Socratic dialogue. “Why do you think that?” followed by “What makes that true?” followed by “What would have to happen for you to change your mind?” That’s where the learning happens.

Affirm the process, not just the conclusions. “That’s a thoughtful way to think about it” matters more than “Right!” You’re developing their reasoning, not just checking their answers.

Make it a dialogue, not an interrogation. Share your own thinking. Admit when you don’t know. Model the intellectual humility you want them to develop.

Keep it low-stakes and enjoyable. Dinner table conversations, car rides, bedtime chats: these are natural settings for Socratic discussions. The goal is engaged thinking, not stress.

When Expert Teachers Help

Socratic discussion is a skill that improves with training and practice. As children grow older and the material becomes more complex, the depth and difficulty of the discussions increase. Leading a conversation about a picture book is one thing. Facilitating a discussion on whether Antigone was right to defy Creon is another.

Many homeschool parents find that they can handle Socratic discussions well in the grammar stage, but appreciate expert help as their children move into the logic and rhetoric stages. Teachers who’ve spent years facilitating Socratic dialogue can push students further and guide richer discussions, especially with challenging texts.

Veritas Scholars Academy offers live online classes where students experience Socratic teaching from trained instructors. You remain the center of your child’s education while drawing on the resources of a broader community. Many families use our Self-Paced or You-Teach curricula for some subjects while enrolling in VSA courses for subjects where they want that expert Socratic instruction.

Common Misconceptions About the Socratic Method

The Socratic method is often misunderstood. Let’s clear up some common misconceptions.

“It’s Just Asking a Lot of Questions”

Not all questioning is Socratic. A teacher who peppers students with factual questions (“What year was the Constitution signed? Who wrote Federalist 10?”) isn’t using the Socratic method. Neither is a teacher who asks questions but doesn’t really listen to the answers.

Socratic questioning is purposeful, probing, and responsive. Each question builds on the student’s previous answer. The goal is discovery, not recall.

“It’s About Trapping People or Making Them Look Foolish”

Bad implementations of the Socratic method can feel adversarial. You may have seen this play out on the silver screen. In the The Paper Chase, for example, a law school professor uses something like the Socratic method to haze his students. This makes for dramatic scenes, but it isn’t good teaching.

True Socratic dialogue is collaborative, not combative. Socrates could be tough on his questioners, but his goal was always their growth, not their embarrassment. A good Socratic teacher creates an environment where it’s safe to be wrong, because being wrong is where learning starts.

“It Only Works for Philosophy or Humanities”

Socratic questioning applies to any subject that involves reasoning, which is every subject.

In science: “What would happen if we changed this variable? How could we test that hypothesis? What evidence would disprove this theory?”

In mathematics: “Why does that formula work? Can you explain your reasoning? What if we approached the problem differently?”

In history: “What caused this event? Could it have turned out differently? What were these people trying to accomplish?”

The core skill, thinking critically about claims and reasoning, is universal.

“Students Just Want to Be Told the Answer”

This is sometimes true, especially at first. Socratic learning is more demanding than passive reception. It requires students to do cognitive work, and work is hard.

But something interesting happens with practice. Students who experience Socratic learning often come to prefer it. They discover that wrestling with a question is more satisfying than being handed an answer. They take ownership of their learning. The initial discomfort gives way to genuine engagement, and we see them rise to the occasion.

Expecting more of students is a sign that you believe they’re capable of more.

Socratic Inquiry and the Christian Mind

For families seeking a distinctly Christian education, a question naturally arises: How does Socratic questioning fit with faith?

The answer lies in understanding the relationship between faith and reason in the Christian tradition.

Faith Seeking Understanding

Christians have never believed that faith means abandoning the mind. From the earliest centuries, Christian thinkers have insisted that faith and reason work together.

Augustine's famous phrase "faith seeking understanding" captures this vision. We believe by grace, through faith. But having believed, we seek to understand. We use our minds in service of knowing God more deeply.

This conviction runs through the Christian intellectual tradition. Anselm and Aquinas used dialectical methods in pursuit of truth. The medieval university, a Christian invention, was built on disputatio: Socratic-style debate about theological and philosophical questions. The Reformers continued this legacy. Calvin was trained as a classical humanist before his conversion, and he brought that rigorous intellectual formation to his theological work. The Reformed tradition produced catechisms that teach through questions and answers, a format that echoes Socratic dialogue and shapes minds through active engagement rather than passive reception.

The conviction underlying all of this is simple: all truth is God's truth. When we pursue knowledge carefully and humbly, we are thinking God’s thoughts after Him, exploring the world He made and the wisdom He has revealed.

Examining Beliefs to Strengthen Them

One of the great dangers for children raised in Christian homes is that they inherit their parents’ faith without making it their own. They believe because Mom and Dad believe. When they encounter challenges in college, in culture, or in their own doubts, their unexamined faith crumbles.

Socratic questioning helps prevent this. By learning to examine their beliefs, students move from assumptions to convictions. They understand not just what they believe but why. They can articulate and defend their faith thoughtfully.

This doesn’t mean reducing faith to a purely intellectual exercise. But it does mean developing the capacity to give a reason for the hope they have, as Scripture itself commands: But sanctify the Lord God in your hearts, and always be ready to give a defense to everyone who asks you a reason for the hope that is in you, with meekness and fear (1 Peter 3:15).

Humility and the Pursuit of Truth

Socratic humility resonates deeply with Christian virtue. That old paraphrase of Socrates’ position, that “I know that I know nothing,” isn’t far from recognizing that human wisdom is limited compared to God’s. We approach truth as seekers, not as those who have arrived.

This posture of teachability, curious, humble, always ready to learn, is entirely compatible with confident faith. We can be certain of God’s love and still have much to learn about how to live faithfully. We can trust Scripture’s authority while humbly acknowledging the limits of our interpretation.

All truth is God’s truth. Inquiry, rightly conducted, is an exploration of the world God made and the wisdom He has revealed.

The Power of a Good Question

The Socratic method has endured for 2,400 years because it works.

It forms minds that can think, not just memorize. It produces students who are curious, articulate, and intellectually humble. It prepares young people for college, career, and calling by teaching them how to learn.

Socrates believed that the unexamined life is not worth living. The examined life, by contrast, is richer, deeper, more fully human. The Socratic method is a tool for examination, for understanding ourselves, our beliefs, and our world more honestly.

Imagine an education where your child isn’t given answers to memorize but guided to discover truth for themselves. Where they learn to ask good questions, examine their own thinking, and engage with the greatest ideas in history. Where they develop wisdom and conviction that will last a lifetime.

That’s what classical education offers. And the Socratic method is one of its most powerful tools.

At Veritas Scholars Academy, Socratic dialogue is woven into the fabric of our curriculum, especially in our signature Omnibus courses, where students engage with the Great Books through discussion rather than lecture. Our teachers are trained in the art of Socratic questioning, and our live classes create the community where genuine dialogue happens.

If you’re looking for an education that teaches your child how to think, we’d love to show you what’s possible. Explore our curriculum, learn more about classical education, or talk with one of our family consultants about whether Veritas is right for your family.

The best education begins with a question. What kind of thinker do you want your child to become?