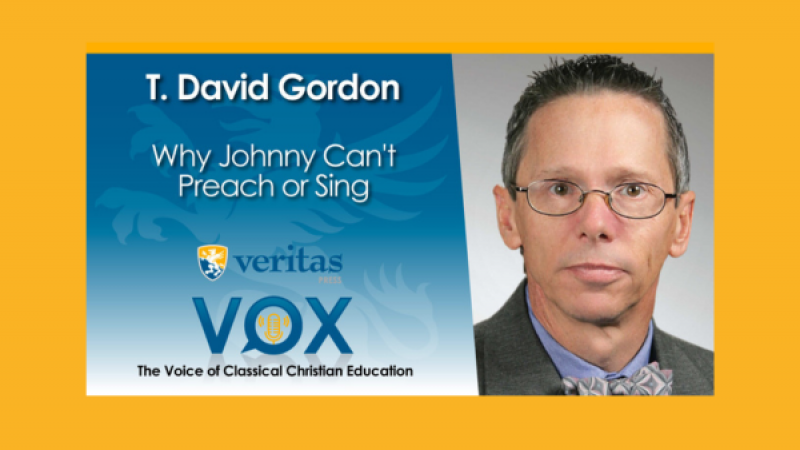

Why Johnny Can't Preach or Sing | T. David Gordon

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Listen on Spotify | Watch the Video

How has modern music and technology changed churches and culture in America? The effects of pop music and smartphones may have shaped the world – even our theology and academics – more than you realize! Join author T. David Gordon for a fascinating conversation on the evolution of our students, churches, and pastors.

Episode Transcription

Note: This transcription may vary from the words used in the original episode for better readability.

Marlin Detweiler:

Hello again, Marlin Detwiler, and you've joined us for another episode of Veritas Vox. Today, we have with us T. David Gordon, Dr. Gordon, a retired professor from Grove City and a man who has been involved in a lot of cultural change and has been addressing it in his career. David, welcome.

T. David Gordon:

Thank you. Marlin, nice to be here.

Marlin Detweiler:

Well, we're so happy to have you here. I want to hear before we get into the topics, tell us a little bit about your background, your family education, and career.

T. David Gordon:

Educationally, having been reared in Richmond, Virginia, attended Roanoke College for a Bachelor of Liberal Arts. Met my wife at a local church there. Became engaged, did two master's degrees at Westminster Seminary in Philly, and then went on back to my native Richmond, actually, to do a Ph.D. in biblical studies under the late Paul Aukenmeyer. And then in 1984, I joined the faculty at Gordon Cornwell, where I taught until ‘98 or ‘99.

We've had three children. Marion was born in ‘86. Grace In ‘88. Dabney In ‘90. Marion died of leukemia when she was 14 weeks old. So we lost her young. And we're very grateful to have two other daughters after that. We have three grandsons.

Marlin Detweiler:

Very good. Very good. Well, you have probably had a lot of our students come through your classes at Grove City, if I'm not mistaken. One year we had ten students graduate from our online school, Veritas Scholars Academy, and go to Grove City. So I'm pretty confident that you've had a number of our students, and I'm really excited to talk about a couple of things here.

Maybe for starters. Tell me what you have seen happen over the decades that you were at Grove City and maybe even before Gordon Conwell. What you've seen in the evolution of students, their preparedness and what their interests have been.

T. David Gordon:

Well, in the last ten years, maybe I would say the decline in my perception was sharp. The decline was gradual. I would say beginning with the Millennium. But by 2012, maybe most of the colleagues I ran into in the faculty lounge were observing that the students were substantially less engaged intellectually than they were before, basically just emotionally, intellectually, less mature than they had been before.

And that corresponds roughly with the advent of the smartphone. The digital world began, of course, and in the mid-eighties you had desktop computers, then laptop computers in the nineties. But it wasn't until the smartphone that you could 24 hours a day be connected to your peers. So what that did to young people is it changed the ratio, the influence of their peers to the influence of their parents, because even in the presence of their parents physically, they were ordinarily either potted up or looking at a smartphone.

And so what happens is their intellectual development, their general knowledge of things, their capacity with language, their ability to sustain a sustained thought. All of that declined fairly rapidly once we had a group here that had had smartphones from an early age.

Marlin Detweiler:

Interesting. Now, you've been known as somebody who has pursued the idea and taught on the idea of media ecology. That's not a term that we're familiar with. I suspect you're touching on that from what you just said. But tell us what media ecology is, and tell us what you have been teaching and learning about it.

T. David Gordon:

Yeah, if you don't mind, Marlin, I'll say something about the origin of the expression and then three things about what it is.

Marlin Detweiler:

Sure, please do. And I know we want to hear that.

T. David Gordon:

The expression Neil Postman studied under Marshall McLuhan when McLuhan was in Toronto, and Neil Postman argued that it was McLuhan who coined the expression. And so Postman continued the use of the term. And now we have the Media Ecology Association, which has been around for 35 or 40 years, in fact. And so it's a very unappetizing, unattractive term, in my opinion.

And yet, we continue to use it because students of McLuhan are familiar with it. But as you can tell from the name, media ecology looks at media not as a business person does in terms of what it will do for us, but the way an archeologist looks at cultural things. What do they do to us, right? What do they do to us?

So it's part of our environment to talk about media ecology, to talk about the human environment with a special focus on what it's like to be in an oral culture that doesn't have handwriting yet. What's it like to have handwriting? So Walter Ong dealt with that in his career. And then what's it like to have a printing press, and how does that alter a culture and so forth?

And so we use the term “ecology” or “environment” because there are two things that people who study biological environments always tell us. One of them, they tell us that ecological change is never additive. Ecological change is never additive. When I returned to northern Vermont to either snowshoe or hike to a cabin up there that I've gone to for years, we do have a few mountain lions in the area now. I've seen their tracks and I saw one with my eyes once. But they're in such small numbers that they haven't changed the forest. If they continue to thrive, however, it will be a different forest 70 years from now than it is today. Because the whole chain of predator and prey will change. So when you add a mountain lion to the forest, you don't have the previous forest plus a mountain lion. Now you have a different forest because he preys on what were predators. And so some of the previous predators are gone. And that means some of the things they ate are gone. And some of the things they ate are thriving. And so all environmental change, people say, is not additive, but total it's comprehensive. So when you add radio to human society, you don't have the previous society plus the radio. You have a different society altogether.

Marlin Detweiler:

It makes sense.

T. David Gordon:

And so that's one of the big things that environmentalists talk about. Media ecologists then talk about how the addition or deletion of certain media to and from a society change the whole environment in that way.

And then the second thing is that all environments encourage certain life forms and discourage other life forms. They don't do it with language, right? But certain forests by what is present in them create little minor mini micro ecologies in which certain species can thrive and which others have difficulty with. And so what we media ecologists then do is they say, “Well when our culture is altered by the presence or absence of a given medium, what kinds of life does it naturally encourage? Either individually considered cognitive development served or socially considered? What kind of connections do we have with one another socially, and what kinds of human attributes do we develop as individuals?”

So all media to change will encourage and discourage certain forms of life. Before the telephone, for instance, most social experience was face-to-face, and then, beginning with the telephone, some of it was not face-to-face. It was at a distance. And, of course, the digital world has increased and changed forever the relation of the proximate and the distant. So that's what media ecology is about.

Marlin Detweiler:

Well, you started by saying you don't like the term. I want to tell you, don't try and change it.

T. David Gordon:

It's a way of viewing the human environment in terms of the presence or absence of certain media.

Marlin Detweiler:

Yeah, yeah. I like the term not because it was intuitively understood by me, but rather it was the putting together of two words that made me curious and want to know more. So I'd say keep the term because that curiosity, I think, is probably a generally positive thing. And it's fascinating to think about that because it makes perfect sense to me that adding the radio or adding television or adding the smartphone is not what we had before, plus. It makes its way into the culture and changes it. It's of a different DNA in some sense, isn't it?

T. David Gordon:

That's correct. In the early days of moving pictures, they were sort of rapidly produced for commercial product profit. And they were fairly primitive by our current standards of production values. But the interesting thing is they found that in towns that had a movie theater, the average person attended the theater three or four times a week.

So they were like nickel movies. And people would go down there, and they would run a movie for two days. They wouldn't run it for two weeks or two months. They would run it for two or three days. So think of how that altered family structures. If two or three times a week, one or another, or several of the family members were not in the home, but they were at the local theater.

And then, of course, with television, movies backed off in their prime because people could stay at home and watch them. So now they're home instead of out somewhere else. But on the other hand, while they're home, they're all sitting there glued to the television, and they're not interacting the way they might have in previous generations.

Marlin Detweiler:

Yeah, the dynamics have implications that are sometimes hard to forecast and have to be managed. And it sounds to me like you've made a study of that. Well, you've made an observation about being prepared and the smartphone really being a moment of change in this media ecology. Has the classically educated kid that you have had opportunity to interact with helped that or has there been no difference in them and their interest in learning?

T. David Gordon:

In my experience, the classically trained student was more different from other peers than he was 20 years ago. That is to say, most of his peers would have been in a family that embraced digital technology without reservation. But because in classically trained schools, the parents have made a choice about their children's education, the parents are therefore more of a party to that education.

Okay. And so the parents in that environment are more wary, I think, of the invasive nature of those kinds of technologies on the family itself. And so what happened is the disparity between the typical public school-educated kid and the classically educated or homeschooled. That disparity might have been here in 2000 and it was here in 2022.

Marlin Detweiler:

Interesting. Interesting. Well, I'm hoping that our efforts at Veritas are raising students who, as they come through our program, go into programs like you've been a part of at Grove City, that they are a bit more self-aware, that they're a bit more connected to history and thinking better and more deeply. I think that that's an indicator of success for us. If we accomplish that, I think we'll have accomplished some of the things we're trying to. Good.

You also taught to the point of of becoming a writer. And I don't know what motivated you to write. There are a couple of books I want to talk about why Johnny Can't Preach and why Johnny Can't Sing Hymns. But what motivated you to write in the first place?

I have you mentioned Neil Postman earlier, and one of the things that was really meaningful to me was when he talked in his best-known book.

T. David Gordon:

Amusing Ourselves to Death.

Marlin Detweiler:

Thank you. You saved my old short-term memory issue there. But he wrote about a car salesman wanting to sell him a car that had electric windows, and he said, I don't want electric windows. What problem does that solve for me? I don't get much exercise as it is. At least if I have to roll the window up, I get a little exercise.

And I thought it hilarious. And the whole idea was as we write something, the question is what problem are we trying to solve? And one of the books you wrote was Why Johnny Can't Preach: The Media Have Shaped the Messengers. What problem were you trying to solve in writing that?

T. David Gordon:

Well, there was personal history there. I got my sense of call to serve the church while I was in late high school. And once you have some sense of a call to serve the church, you attend church differently than other people do. Right. Because you're an aspirant the way if you're thinking of becoming an auto mechanic, you watch it as a mechanic.

When he works on your car and you're very interested in the tools you use and how he goes about it. So I would say that most people who are aspirants for the Christian ministry begin to be critical in their evaluation of the church, not critical in a negative sense, for instance. Right. Because to be truly critical is to judge.

And if a person has a good ministerial style, you make a checkmark mentally and say, Oh, he's an approachable human being and as an ambassador of Christ, he ought to be approachable. Right. So to be critical means you're just constantly assessing because you want to learn the good things. And then if there are a few negative things you observe, you want to avoid them.

And what I noticed for probably 20 to 25 years is pretty poor preaching. And I thought it was merely subjective until in one calendar year, in the early eighties, I talked to two elders on two different occasions from two different churches who were serving on pulpit committees at the time. And in my conversations saying, “How's it going?”

Two totally separate cases, two different individuals, they said, “Well, we just accept the fact that we won't find a good preacher. So we're looking for a man who has other good traits.” And in that way, I realized I wasn't the only one who had that perception. So I then read Robert Louis Dabney's lectures on sacred Rhetoric, in which he mentioned seven cardinal requisites of a sermon.

So not seven excellences, but seven cardinal requisites, things that just had to be in every sermon. And as I then kept my critical gaze, I was noticing that I rarely saw a sermon that had all seven. And I often heard sermons that didn't have any of this effort. Right. Wow. So then I realized it wasn't just my subjective appraisal that here's a standard textbook on preaching from the 19th century, and almost no one is hitting all seven and many people aren't hitting any of them.

So I hid these things in my heart, as it were, for a number of years, because I didn't want to appear to be critical in the negative sense of the term. But then when I was diagnosed with stage three colorectal cancer early in 2004, with about a 25% chance of living, I realized I had to try to say this before I died.

Marlin Detweiler:

Yeah.

T. David Gordon:

And so I decided that on the few days that I had some energy, I might start whittling away at addressing this from my immediate ecological point of view, I suppose. And so I worked at it and was probably 80% done with the book by the time 11 months later the cancer treatments ended and I did survive. I mean, I lost 35lb along the way.

And if you're 5’3, that's a lot of weight to lose. Came close to dying a couple of times, but did live! And so then I decided as I was catching back up to my regular professional duties, I would keep working on the book till I could finish it. And so I sent it off to several publishers who said it doesn't fill a marketing niche. But then, when I sent it to Marvin Padgett at PNR, he said he was going to go out on a limb with his board and tell them they needed to publish this because it needed to be said. And since then, I have found that many theological seminars are requiring it of their students.

Marlin Detweiler:

Is that right?

T. David Gordon:

Sometimes, seminaries way outside of my connections, I'm talking even Dr. MacArthur and all his students. He requires that of all of his MDIV students and several of the Southern Baptist schools require it of their students, and some of the reformed seminaries require it of their students. So once it was in print, apparently it's gotten a pretty good read.

Marlin Detweiler:

Yeah, that is wonderful! My observation for the church, you know, I am a lifelong Christian in the sense that my parents were Christians. I was raised in the church. I was raised in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in a small Mennonite church. My pastor, growing up was bi-vocational. He was an electrician. He was an uneducated man. But he could preach.

I bet if I asked him, could you train someone else to preach, he wouldn't know where to start.

But intuitively, he knew how to preach. Interestingly, today, we're part of a PCA Church, Presbyterian Church in America. And our pastor here is a remarkable preacher, one of the top three or four preachers I've heard with any regularity. And he's remarkable. I've also asked him, “Have you ever thought of trying to bottle that stuff, help others learn how to do it, so to speak?”

And he kind of laughed. He said, “I don't know if I could do that.” It's interesting. Sounds to me like you're really on to something. Is it the list of seven attributes of a sermon in the book that you've written?

T. David Gordon:

Yes. It took Dabney two chapters to do those. I put four in one chapter and three in the others. But for four of his traits, I'm going to list them in my order, not his. Four of his traits would be true of any public discourse. Three are distinctive to preaching. Okay, so public discourse should have unity that if you asked ten people afterward, what was this talk about?

Let's say someone gives it at Toastmasters International or the Rotary Club, or one of these other places. If there's a public talk, there should be enough unity that at least nine out of ten people could tell you what it was about. It should have what he called order. That it should move from certain portions to other portions in a certain order, because in a public discourse, certain things need to be said early.

We define ourselves early because if someone misunderstands like media ecology, if someone didn't know what that was about and we continue the conversation, then they couldn't follow what comes later, he said, the second attribute is order or arrangement. Right.

A third thing he says is movement. Once you have made a point adequately, you need to move because otherwise, you lose people because effectively, they're saying, “Okay, I've got you now, I've got it already.” So we do this kind of motion with people. Sometimes we're saying to get people going right.

And then the fourth, which he mentions as a fourth trait, and I don't think it is a fourth trait I think is the result of the other three. He calls it point. And what he means is like the point of an ancient battleship where all the lumber is structured in a certain way. If it was a ramming vessel, it would arrive with all of its point. I think that's really the result of having unity, order, and movement. It will naturally have a point, but that's okay. I'm not going to argue with you.

Now, the three points that he thinks that a sermon ought to have different than any other public discourse, are it should be expository, plainly based on the holy Scripture, it should be gospel-centered– I think he called this evangelical in tone. That is to say, the whole thing should be a winsome presentation of the adequacy of Christ as Redeemer to save to the uttermost those who come to God through him, something like that. And a third quality, he said, is it should be instructive. So, in addition to being expository, based on the authority of God's Word, it should help people to understand that part of God's Word in the overall scheme of everything else.

So a passage of Scripture is still part of that great narrative of redemption that starts in the fall and comes all the way to the close of Revelation 22. So, to help people understand that passage in its canonical and redemptive-historical context, you see is also a part. So a good sermon there. Then differently from a public talk on other matters has to be expositional to have the authority of God's Word. It has to be instructive so people understand what's going on. And it should be evangelical in tone or winsome or Christ-centered. That's it that the whole thing should point to God's redemptive work in Christ in some way. And so those seven traits I think, are still very good traits. And they are the seven traits that I didn't see for years in preaching. Occasionally, I would see one or two of them, but not the others – and Dabney said you should have all seven.

Marlin Detweiler:

That is really encouraging. I am so glad to hear that seminaries have adopted it and use it and I hope the students will increasingly apply it. You know, my entrepreneurial sense that operates with I know there's something wrong, but until I can define it in words or ideas, it's very hard to act on fixing it.

And you've really defined very well what I think is missing in one of the most important aspects of any kind of public discourse. It's life-changing when you have a pastor who can preach.

T. David Gordon:

Right! It is.

Marlin Detweiler:

And our church needs it desperately.

T. David Gordon:

Yeah, it certainly does. And you'll be gratified to know that one of my former Gordon Conwell students, who was himself a minister after he read the book and thought about it for a couple of years, he left the ministry to become the headmaster of a Christian school because he realized that the traits necessary to becoming a good preacher had to be cultivated at the academic level beforehand.

So, for instance, how can a person exposit holy Scripture if he doesn't know how to read text? He has to read texts, even ancient texts, right? Training and training and poetry and even classical rhetoric and so forth. Teach people to do that. And if people don't write handwritten letters or typed letters anymore, but they send briefer things, you see, they're not used to composition, but you see in a Christian school, in an environment such as Veritas, you can teach people to read carefully and to write intelligently. And these are the pre-hermeneutical skills a minister needs.

Marlin Detweiler:

Absolutely. I have often thought, you know, here I am, 67 years old, still functioning in my role for 29 years at Veritas, and wondering what would I do or what will I do when I'm done. And I've often thought, take the next step and work with the graduates. More informally. But these kinds of things are really exciting and encouraging.

You've written another book. We're running out of time. How to make sure we get this in too - Why Johnny Can't Sing Hymns: How Pop Culture Rewrote the Hymnal. What problem were you trying to solve there?

T. David Gordon:

Yeah, the problem there. And by the way, you'll notice that the theft in the title, both books were indebted to Rudolph Fleischer's book, Why Johnny Can't Read.

Marlin Detweiler:

I knew that.

T. David Gordon:

Many people didn't realize that, and they wonder where that came from. But the subtitle was What I was Really About. So, in the first one, it was how the media have shaped the messengers, right, regarding preaching. But in this one, is how pop culture rewrote the hymnal. And so the fundamental thesis is this musicalologist were different than musicians.

Musicologists study the history and philosophy of music. Musicologists all agree that the period from 1890 to 1930 was what David Sweetman at the University of Delaware, Wilmington. He called it “the revolution in music” because music was always alive. It always had a human attached to it from Adam until roughly that period with the player piano and the gramophone and so forth, and more so not only did it have a human attached, in about 98% of the cases, we performed our own music. All music was folk music because in the days of Bach and Handle and Mozart and so forth, if you didn't live in a large metropolitan city like London or Vienna or New York or Philadelphia or Boston, you would have never heard a performing musician because only a large city could afford them.

And remember, urbanization is a 20th-century movement. So prior to the 20th century, most humans did not live in cities. And as of about five years ago, around the world, most humans now live in cities. But when people were living rural, they weren't near a place where they could see performing musicians, and they didn't write. So people produced their own music.

And so what happened in the 20th century, the revolution was not that that we took down Classical as the king of music. We took down folk music as the king of music, and we replaced folk music with mass-produced commercial music that's designed to be cheap and inexpensive to produce. That doesn't require much of the artist, doesn't require much of the person who manufactures it, and it doesn't require any learning curve on the part of the hearer.

And so then, because we didn't outlaw it, people could publish it wherever they wanted. When you're getting gas while you're pumping your gas, you're listening to it in the background. When you're shopping for groceries, you're listening to it. You go to a restaurant for dinner; you listen to it. So this unsolicited music is now the environment in which we live.

And so just as it's natural for an American to speak English, it's natural for them to think that's what music sounds like. And so when they attend church, they hear music that is the product of many generations, both in terms of its lyrics and, at times, in terms of its musical style. And so it doesn't sound like music to them.

And so there was this movement to abandon all of the traditional hymns and to create a new body of liturgical music that sounds like what we hear when we're pumping gas, which isn’t really sacred. Music ought to sound sacred. It shouldn't sound like what you listen to when you're pumping gas, right?

Marlin Detweiler:

Following the wrong leader never gets us to the right place.

T. David Gordon:

No, never does. So my book tries to explain how our sensibilities were changed by the omnipresence of commercially driven pop music and why the church, somewhat unwittingly and naively, capitulated to it.

What we should have just said to people, “Look, there's a learning curve to listening to a sermon. There's a learning curve to learning the Nicene Creed or the Apostles Creed. And what they mean is a learning curve for a five-year-old to learn the Doxology, though he doesn't read yet, right?”

The Christian liturgy has a learning curve and let's just deal with it. That's not a tune that this one section has to sound like. What we do for the most mundane amusement all day long. It should sound luminary and sublime. It should not sound mundane. It should be different.

Marlin Detweiler:

Well, we have run out of time and there are so many directions. I would love to take this with you, T. David, Thank you so much. I hope and I'm sure you've inspired the listeners to take a hold of those books and and to take this further. And maybe that's what we should aspire to hear, because we're certainly not going to cover this all in one, two or, three 30-minute episodes. Thank you so much for joining us today.

T. David Gordon:

It's been great to be with you, Marlin, and thanks for your good work with Christian education, because that's what educators need at the college and seminary level, is people who've been educated before.

Marlin Detweiler:

I've often said that if we wait until college to try and capture what they need to learn, it's too late. Thanks for joining us on Veritas Vox, the voice of classical Christian education. Once again, we've had T. David Gordon with us. Thank you so much.

T. David Gordon:

Yeah, it's good to be here, Marlin. Thank you.