Classical Education: The Complete Parent’s Guide

You’ve probably felt that nagging sense that something is missing from modern education.

Schools seem increasingly focused on standardized tests, career preparation, and checking boxes.

But what about teaching students to actually think? To wrestle with big ideas? To become more than just employable adults, but wise, capable, articulate human beings?

If you’ve had that feeling, you’re not alone. And you’re not imagining it. You know your child. You’re the one asking the hard questions about their education. That instinct is exactly right.

What if there was an approach to education that had been doing exactly this, forming students who can think clearly, communicate persuasively, and learn anything?

Good news! There is. It’s called classical education, and it’s experiencing a resurgence among families who want something deeper for their children.

This guide will walk you through everything you need to know. We’ll define classical education and discuss its origins, how it works, and whether it might be right for your family.

Whether you’re a seasoned homeschooler exploring a new approach to your student’s education, a parent considering alternatives to traditional schooling, or simply curious about this method, you’ll find clear answers here.

What Is Classical Education?

At its core, classical education is a method of teaching that focuses on how students learn, and not just what they learn. Rather than treating education as the mere transfer of information from teacher to student, classical education aims to give students the tools they need to learn anything for the rest of their lives.

The Liberal Arts

This approach is rooted in the liberal arts tradition of the ancient world, of Greece and Rome and early Christendom. This is the same tradition that shaped the great thinkers, leaders, and artists of Western civilization for centuries.

The word “liberal” here doesn’t refer to politics; instead, the term comes from the Latin liber, meaning “free.” A liberal arts education was the education befitting a free person, a citizen, someone who could think for themselves, govern themselves, and participate in society.

The Trivium

Classical education emphasizes three foundational skills:

the ability to gather and organize information,

the ability to reason through problems and evaluate arguments,

and the ability to communicate ideas persuasively.

These aren’t separate subjects so much as integrated skills that develop over time, and they form the basis of what’s called the “trivium,” which we’ll explore in detail shortly.

Unlike modern education, which often fragments human knowledge into disconnected subjects, classical education integrates learning around a unified pursuit of truth. History, literature, science, theology, philosophy. These aren’t isolated silos but facets of a coherent worldview. Students learn to see the relationships between ideas, to trace themes across centuries, and to ask the kinds of questions that matter most:

What is true?

What is good?

What is beautiful?

The Goal of Classical Education

The goal isn’t simply to produce students who can pass tests or gain admission to colleges, though classically educated students often excel at both. The deeper and greater aim is formation, shaping the whole person, including mind, character, and soul.

Classical education produces students who can think critically about complex issues, communicate their ideas with clarity and conviction, engage thoughtfully with people who disagree with them, while pursuing truth wherever it leads. This educational methodology prepares students not just for their first job after college, but for the full range of callings they’ll encounter as citizens, parents, neighbors, and people of faith.

As Dorothy Sayers argues in her influential essay “The Lost Tools of Learning,” the goal is to teach students not what to think, but how to think.

Give a student that foundation, and they can learn anything.

“Is it not the great defect of our education today that although we often succeed in teaching our pupils ‘subjects,’ we fail lamentably on the whole in teaching them how to think?” —Dorothy Sayers, The Lost Tools of Learning

The History of Classical Education: From Ancient Greece to Today

Classical education isn’t a modern invention. It’s the oldest continuous educational tradition in Western civilization, and understanding its history helps explain why it still works.

Classical Education in the Ancient World

The roots of classical education reach back to ancient Greece, where philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle developed systematic approaches to forming young minds.

The Greeks had a word for this: paideia, which encompassed not just academic instruction but the holistic formation of citizens capable of participating in public life.

Paideia (noun): Training of the physical and mental faculties in such a way as to produce a broad enlightened mature outlook harmoniously combined with maximum cultural development. —Merriam-Webster

The Romans adopted and systematized Greek educational methods, developing what became known as the seven liberal arts. These were divided into two groups: the Trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) and the Quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy). The Trivium provided the foundational skills for all further learning, while the Quadrivium applied those skills to understanding the natural world.

The Romans believed that mastering these arts was essential for any citizen who wished to participate meaningfully in society to understand the law, engage in public debate, and contribute to the common good.

Classical Education Through the Middle Ages and Renaissance

When the Roman Empire fell, the tradition of classical education could have been lost. Instead, it was preserved and transmitted by Christendom.

Monasteries became centers of learning where monks copied ancient texts by hand, studied the liberal arts, and trained the next generation of scholars. Later, the great medieval universities—Oxford, Cambridge, Paris, Bologna—were built on the classical model. Students first mastered the trivium before proceeding to advanced study in theology, law, or medicine. The assumption was that you couldn’t properly study anything else until you had learned to think, reason, and communicate.

The Renaissance brought renewed interest in classical texts and methods. Humanist scholars returned to Greek and Latin sources. The greatest minds of this era, from Leonardo da Vinci to John Milton, were products of classical education. Isaac Newton, Galileo, and the scientists who launched the modern age were all classically trained.

The Rise and Fall and Rise of Classical Education

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, educational theory took a different turn.

Progressive educators like John Dewey questioned the classical emphasis on content knowledge and formal reasoning, advocating instead for experiential learning and practical skills. Schools gradually abandoned Latin, reduced emphasis on rigorous writing instruction, and fragmented the curriculum into specialized and disconnected subjects.

By the mid-twentieth century, classical education had largely disappeared from the mainstream.

But a revival was coming.

In 1947, Dorothy Sayers, the British novelist and scholar, delivered a famous address at Oxford titled “The Lost Tools of Learning.” She argued that modern education had failed because it no longer taught students how to learn. The solution, she suggested, was a return to the trivium, adapted, of course, for modern circumstances.

Sayers’ essay circulated among educators and homeschoolers and kicked off a classical revival. Classical Christian schools started opening across the country, and homeschool families adopted classical curricula.

Today, thousands of schools and tens of thousands of families follow the classical model, and accredited online programs like Veritas Scholars Academy make rigorous classical education accessible to students anywhere in the world.

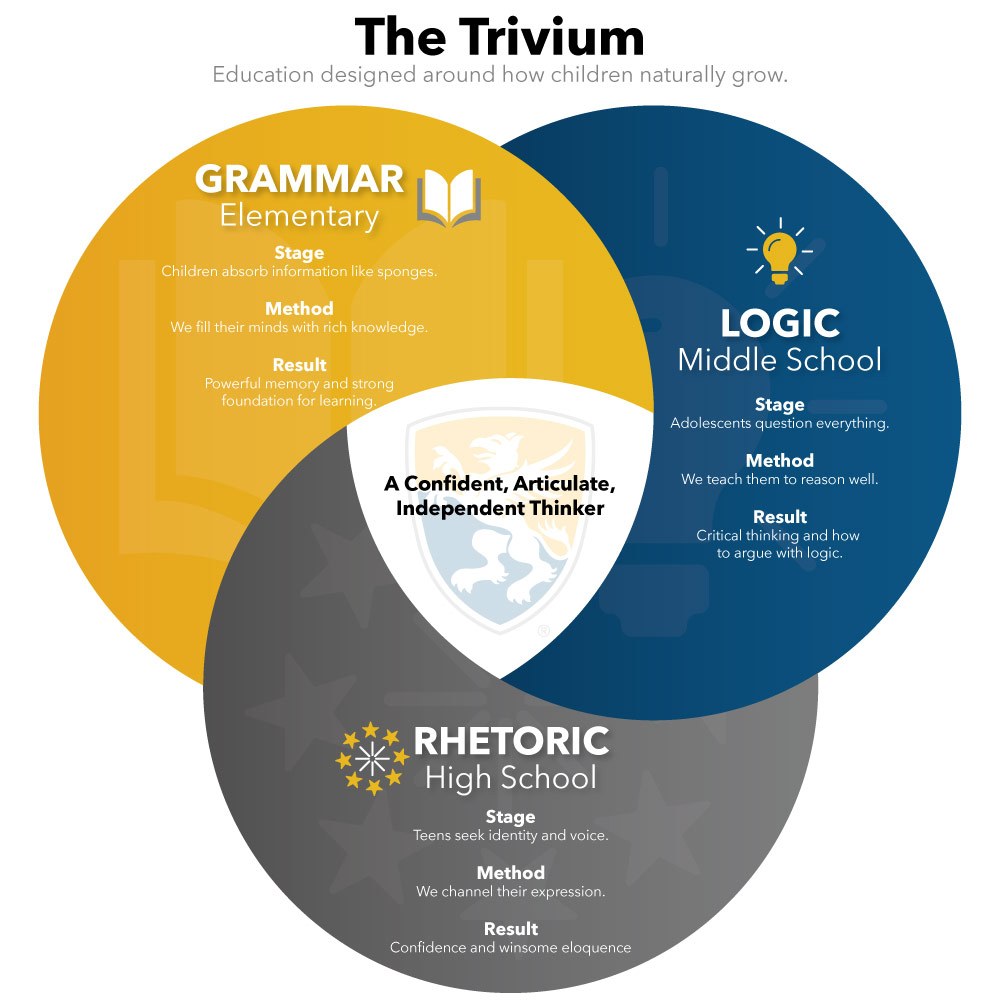

The Trivium: The Three Stages of Classical Learning

If there’s one concept that defines classical education, it’s the trivium.

The trivium is a powerful framework for understanding how children learn at different stages of their development. Young children learn differently than middle schoolers, who learn differently than high schoolers.

Classical education recognizes this and structures instruction accordingly. Each stage builds on the previous one, creating a progression that develops students’ intellectual capacities over time.

The Grammar Stage (Roughly Grades K–6)

Young children have a remarkable capacity for absorbing information. They’re natural memorizers; think of how easily they learn song lyrics, sports statistics, or names of dinosaurs, delighting in facts, patterns, and repetition.

This is the grammar stage, and classical education leans into it.

In this stage, students build a foundation of knowledge across every subject.

They memorize math facts, grammar rules, historical timelines, science vocabulary, and Bible verses. They chant Latin conjugations and sing history songs. They read widely, immersing themselves in classic children’s literature and stories from history.

The goal? Grammar builds the mental foundation that students will use later when they begin to reason, analyze, and create.

You can’t think deeply about history if you don’t know any historical facts. You can’t write well if you don’t understand grammar. You can’t do higher math if you haven’t mastered basic operations.

For many homeschool parents, this stage feels natural. Young children are wired for exactly this kind of learning, and teaching them is often joyful. The challenges typically come later.

The Logic Stage (Roughly Grades 7–9)

Around middle school, something shifts.

Children who once happily absorbed facts now want to know why. They become argumentative—sometimes maddeningly so (“Actually, Pluto isn’t a planet anymore. Actually, you said we’d leave at 3:00, and it’s now 3:02. Actually . . . ”). They question everything, challenge authority, and delight in pointing out inconsistencies.

This is the logic stage (sometimes called the dialectic stage), and rather than fighting it, classical education harnesses it.

If students naturally want to argue, teach them to argue well from a defensible position supported by facts and clear observations. If they’re fascinated by cause and effect, help them trace those connections systematically.

In this stage, students learn formal logic: the structure of valid arguments, common fallacies, and the rules of sound reasoning. They practice Socratic discussion, learning to ask probing questions and defend their positions with evidence. They analyze primary sources, comparing historical accounts and evaluating competing interpretations.

The facts they memorized in the grammar stage now become material for reasoning. Instead of simply knowing that Rome fell in 476 AD, they explore why it fell and what lessons that holds for today. Instead of memorizing a poem, they analyze its structure, imagery, and meaning.

Many parents find this stage rewarding but demanding, and wisely bring in expert teachers to partner with them. Teaching formal logic, facilitating Socratic discussions, and guiding rigorous analysis requires different skills than reading aloud and supervising memorization.

The Rhetoric Stage (Roughly Grades 10–12)

High schoolers are developing their own voices. They have opinions, they want to be heard, and they’re beginning to think about who they want to become. The rhetoric stage channels this drive toward eloquent and persuasive communication.

If the grammar stage asks “What?” and the Logic Stage asks “Why?”, then the rhetoric stage asks “So what?” and “How can I communicate this effectively?”

Students synthesize what they’ve learned across disciplines, develop original arguments, and learn to express complex ideas with clarity and power.

This developmental stage emphasizes writing, especially thesis-driven essays and research papers, and public speaking. Students learn to craft compelling arguments, anticipate objections, and move an audience.

Great Books also play a central role here. Students engage directly with the foundational texts of Western civilization (Homer, Augustine, Shakespeare, Bunyan, and beyond), wrestling with the biggest questions humans have ever asked. They read the texts themselves and join a conversation that spans millennia.

By the end of the rhetoric stage, students aren’t just prepared for college—they’re prepared for life. They can think, write, and speak. They have a coherent worldview and the confidence to express it. They can learn anything because they’ve practiced the tools of learning.

Why the Trivium Works

The genius of the Trivium is that it aligns with how children actually develop. It doesn’t fight against their natural inclinations at each stage but works with them.

Young children love to memorize, so we give them things worth memorizing.

Middle schoolers love to argue, so we teach them to argue well.

High schoolers want to express themselves, so we help them find their voice.

Each stage builds on the previous. The facts of the grammar stage become the material for analysis in the logic stage, which becomes the foundation for synthesis and expression in the rhetoric stage. It’s a cohesive progression, knowledge building upon knowledge.

The result? Students who can learn anything because they’ve learned how to learn.

What Makes Classical Education Different?

If you’re coming from a conventional school background, or if you’ve been homeschooling with more standard curricula, you might wonder what really sets classical education apart.

Several core ideas make classical education different.

Integration vs. Fragmentation

Although there have been attempts to remedy this situation through interdisciplinary learning in recent years, modern education tends to treat subjects as disconnected silos.

Classical education takes the opposite approach, integrating topics around a unified pursuit of truth. They’re tackling more complex mathematics. They’re not just calculating, but constructing proofs that demand logical precision. They’re reading the arguments of great thinkers, tracing how Plato built a case or how Aquinas dismantled an objection. And they’re forming arguments of their own, learning that “because I think so” won’t survive a classroom debate.

This integration stems from the reality that knowledge itself is unified. Truth doesn’t divide neatly into academic departments. Classical education helps students see the relationships between ideas and develop a coherent view of the world.

Formation vs. Information

Conventional education often focuses on information transfer: get the facts into students’ heads so they can perform on tests.

Classical education aims at something deeper: formation of the whole person.

This means that character and virtue are explicit goals and not afterthoughts. Classical education cares about who students are becoming, and not just what they know, asking questions like:

Are they becoming wise?

Are they developing intellectual humility?

Can they pursue truth even when it’s inconvenient?

Do they have the courage to stand for what they believe?

Primary Sources and Great Books

In many schools, students learn about history and literature through textbooks, such as summaries and interpretations written by contemporary authors. Classical education takes a different approach. It goes straight to the source.

Students read Homer, not summaries of Homer. They study Plato’s dialogues, not a textbook chapter about Greek philosophy. They engage with Augustine, Aquinas, Shakespeare, and the great thinkers who shaped civilization. Students get to join the conversation directly rather than hearing about it secondhand.

Great Books programs, like Omnibus, weave together history, literature, theology, and philosophy around primary texts. Students discover that the questions humans wrestled with two thousand years ago are still the questions that matter today—and they develop the tools to engage those questions themselves.

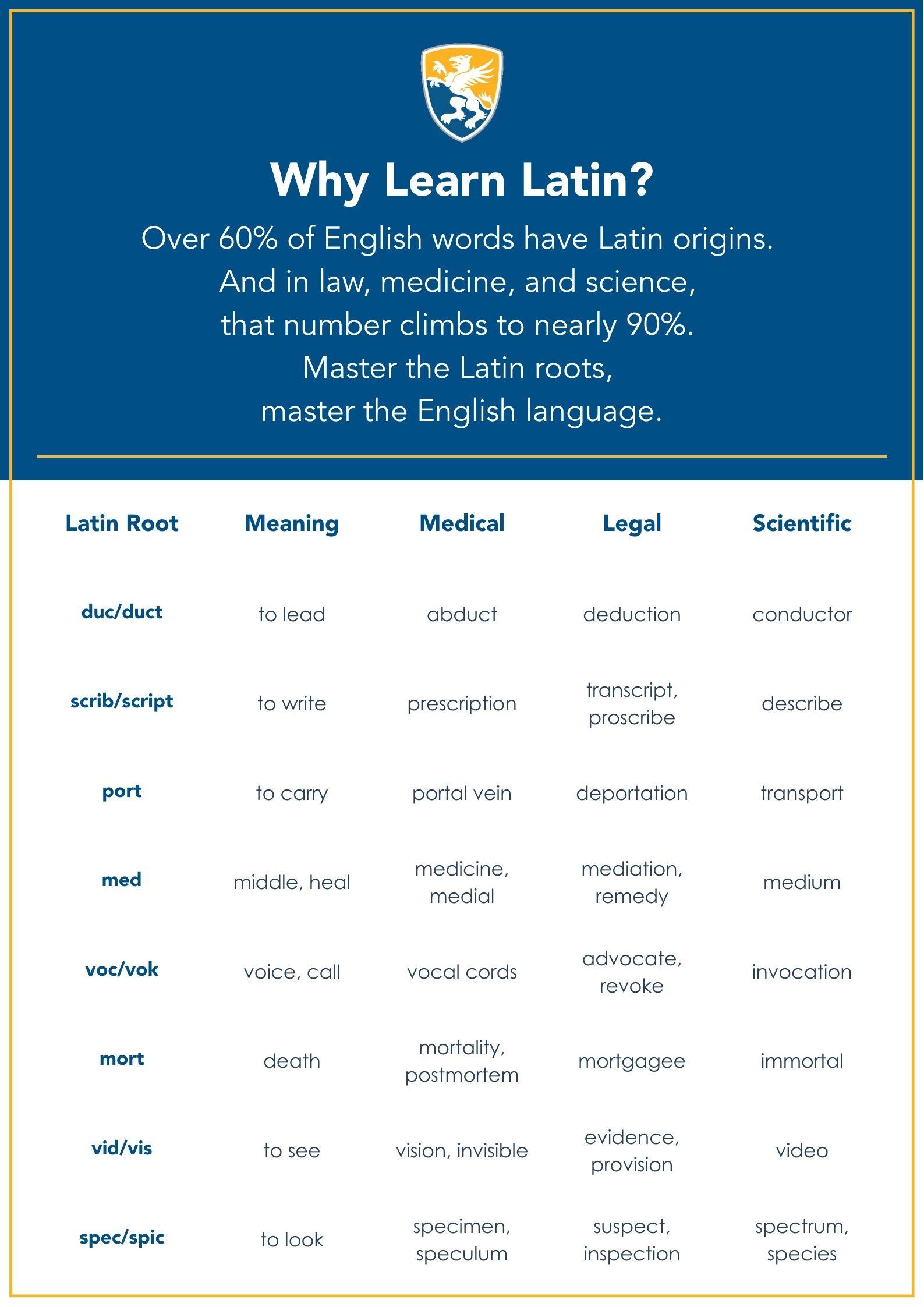

The Latin Question (or the Role of Language)

Parents often ask why Latin still matters in the twenty-first century.

Isn’t it a dead language? What’s the practical benefit?

The case for Latin is stronger than many realize. Latin isn’t truly a dead language. Rather, Latin is the grammar of grammar, teaching students how language works at a structural level, expanding their English vocabulary, and preparing them to learn other languages more easily. In fact, according to the College Board's annual College-Bound Seniors reports, students who studied Latin consistently outperformed students of all other foreign languages on the SAT verbal section.

Students who study Latin consistently outperform all other language students on the SAT, scoring 60+ points higher in Critical Reading.

For example, when students learn that puella (girl) becomes puellam when the word is a direct object, they’ll grasp what “direct object” actually means, as something that changes how a word functions. English relies on word order to convey this (“The dog bit the man” vs. “The man bit the dog”), so native speakers often struggle to articulate why it matters. (Have you ever wondered what the difference is between “who” and “whom”? “Whom” is the indirect object!)

Roughly 60% of English words have Latin roots. A student who learns porto (to carry) suddenly has a key to unlock transport, portable, export, import, report, and deportation. Learning specto (to look) illuminates spectator, inspect, spectacle, respect, and circumspect.

Beyond vocabulary, Latin teaches grammar at a structural level. Because Latin is highly inflected (word endings change based on function) students must understand grammar to read anything at all. This deep grammatical knowledge transfers to English writing, helping students construct clearer, more precise sentences.

Latin also provides a foundation for learning other languages, especially the Romance languages (Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese) that descended from it. And the mental discipline required to master Latin—attention to detail, systematic analysis, careful reasoning—develops habits of mind that benefit students across every subject.

Classical Christian Education

Classical education provides the method. Christian faith provides the meaning. Together, they form students who can think deeply and live faithfully.

A Biblical Worldview in Every Subject

In classical Christian education, faith isn’t confined to Bible class or chapel. A biblical worldview permeates every subject, because all truth is God’s truth.

History becomes the unfolding of God’s redemptive plan, a story with purpose and direction. Science becomes the exploration of God’s creation, revealing the order, beauty, and wisdom built into the natural world. Literature becomes a window into the human condition, illuminating our need for grace and the universal themes of sin, redemption, and hope. Even mathematics reflects the order and consistency of a rational Creator.

This integration means there’s no tension between what students learn in school and what they learn at home or church. The worldview is consistent. Parents don’t have to “undo” anything at the dinner table. They can build on what their children are learning.

The Pursuit of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty

Classical education orients itself toward three transcendentals: truth, goodness, and beauty.

For Christians, these transcendentals are grounded in the character of God, the source of all truth, the standard of all goodness, and the author of all beauty. Education is a way of knowing God better through his works and his world.

This pursuit gives education a depth and purpose that utilitarian approaches lack. Students are formed to see the world rightly and to live in it wisely.

Character Formation and Virtue

Whereas some modern philosophies of education see the students as a means to an end (radical philosophies see students as agents of societal change, while progressive philosophies see students as future citizens and workers), classical Christian education places the student first.

With the whole student in mind, including their will and their heart, classical Christian education cultivates virtue. Through the habits of daily school life, through engagement with great literature and ideas, through community and mentorship, students are shaped into people of character.

The goal is graduates who are not only intellectually capable but morally grounded, prepared to lead, serve, and make a difference in whatever calling God places before them.

The Benefits of a Classical Education

Theory is important, but outcomes matter. What does classical education actually produce?

Academic Excellence

Classically educated students consistently demonstrate strong academic performance. They score well on standardized tests because they’ve developed deep knowledge and genuine intellectual skills.

Their writing stands out. Years of grammar instruction, logic training, and rhetoric practice produce students who can construct clear arguments and express complex ideas with precision. College professors often comment that classically educated students are unusually prepared for college-level writing.

Their knowledge base is broad and deep. They understand how ideas connect across disciplines and across centuries. This integrated knowledge makes them flexible learners who can master new subjects quickly.

College and Career Readiness

Classical education graduates gain admission to the nation’s most selective universities—Harvard, MIT, Cornell, Notre Dame, the U.S. service academies—and they arrive ready to thrive.

$45,000

Average amount in scholarships and grants earned by Veritas Scholars Academy graduates

They’ve already read the Great Books that other students encounter for the first time in seminars. They know how to engage in Socratic discussion, write a thesis-driven essay, and defend their ideas under questioning.

They also earn significant scholarships. Veritas Scholars Academy graduates, for example, receive an average of $45,000 in scholarships and grants per graduate, a testament to the academic records and well-rounded profiles that classical education develops.

But college is just the beginning. Classical graduates succeed in every field imaginable: medicine, law, engineering, ministry, business, the arts. The tools of learning they’ve acquired make them adaptable, capable of excelling wherever their calling leads.

Lifelong Learning and Character

Perhaps the most important outcomes are the hardest to measure. Classical education produces people who love learning, not because they have to, but because they’ve discovered how rich and rewarding it is to explore ideas.

It produces people of wisdom, not just information. Graduates know how to think through complex decisions, weigh competing considerations, and act with integrity even when the path isn’t clear.

And it produces people of character prepared not just for career success, but for the challenges and responsibilities of citizenship, family, and faith. This is education for life, not just for the next test.

Is Classical Education Right for Your Child?

By now, you may be wondering whether classical education is the right fit for your family.

Any significant educational decision deserves careful thought. Here are the questions we hear most often from parents weighing this choice.

Common Questions Parents Ask

“Is my child too old to start?”

It’s never too late!

Students can enter classical education at any stage. While starting in the grammar years is often ideal, the principles of the trivium apply at any age, and students adapt to the expectations and methods more quickly than you might expect. Many families begin in the logic or rhetoric stage and see remarkable growth.

That said, classical education holds students to a high standard. Families who make the switch in middle school or later sometimes find their student needs time to catch up to classical peers, particularly in writing and Latin, but sometimes even in math and science. This isn’t a roadblock. With parental direction and support from experienced teachers, students who put in the effort find classical education both doable and rewarding.

“Do I have to teach this myself?”

Not necessarily.

Classical education comes in many forms: self-paced, parent-taught, and even online schools with teachers and live classes. At Veritas Press, we offer all three ways to learn: Self-Paced, You Teach, and Veritas Scholars Academy, which families can attend full-time, earning a diploma, or part-time, supplementing their other studies.

So, if the idea of teaching formal logic or leading discussions about Great Books feels daunting, you’re not alone. And you have options. Programs like Veritas Scholars Academy provide live, interactive classes taught by experienced teachers, allowing your student to receive a rigorous, accredited classical education while you focus on other aspects of family life.

That might mean time to work one-on-one with a younger sibling who’s learning to read, or the mental space to plan a history unit you’re actually excited about. It might mean your relationship with your teenager isn’t strained by nightly battles over Latin declensions.

“Will this prepare my child for college?”

Absolutely. In fact, classical education tends to over-prepare students for college. The writing, reasoning, and communication skills they develop exceed what most high schools provide. Accredited classical programs like Veritas Scholars Academy ensure transcripts and diplomas are recognized by colleges and universities nationwide.

“What if my child struggles with certain subjects?”

Classical education meets students at their current level and develops their capacities over time. Many students who struggle in conventional settings thrive in classical education because of its coherent structure, its integration of subjects, and its emphasis on understanding over memorization.

Personalized academic planning can help tailor the path for students with different strengths, challenges, or learning styles.

Signs Classical Education Might Be a Great Fit

You might be a great fit for classical education if you find yourself nodding along to these:

I want to prepare my child for life.

I want my child to learn how to think, not just what to think.

I want my child to realize their full potential.

I want my child to become thoughtful and articulate.

I want my child to wrestle with important ideas.

I want my child to ask better questions and discover the answers.

I want an education that makes sense of the world.

I want my child to value truth and beauty and goodness.

If that sounds like you, classical education deserves a serious look.

The Education Your Child Deserves

Classical education is a return to what has worked for centuries, a proven approach to forming students who can think, communicate, and lead.

It prepares students for more than college admissions and career success, though it accomplishes both. It prepares them for life: for the decisions they’ll face, the relationships they’ll build, the responsibilities they’ll carry, and the calling they’ll pursue.

The investment pays dividends for decades. Students who learn how to learn can master anything. Students who have wrestled with the great questions are equipped to navigate complexity. Students who have been formed in virtue are prepared to lead with integrity.

And here’s the encouraging news: you don’t have to do it alone.

For over 27 years, Veritas Press has been helping families around the world deliver rigorous classical Christian education, through self-paced courses, parent-taught curriculum kits, and our accredited online classical Christian school, Veritas Scholars Academy. We offer award-winning curriculum, live online classes, and a fully accredited K–12 school, so you can build the education that fits your family and grow with it as your needs change.

You’re making one of the most important decisions for your child’s future, and we’re here to support you on your journey.