Charlemagne's Gift to Classical Education

As the 8th century drew to a close, Western Europe was rapidly united for the first time since the height of the Roman Empire. Charles, son of Pepin the Short, had inherited the Frankish kingdom and his father’s loyalty to the Church. It was not long before Charles began a wave of victories as he conquered country after country, growing the Frankish Empire.

Charles’ administration was straightforward in its autocratic nature but as a son of the Church, he nevertheless saw his continuing victories as uniquely given by Christ. Because of the weight of this responsibility, Charles, who had been uneducated, recognized that the only way to establish this budding empire he had been given was through mind and church rather than merely by the sword.

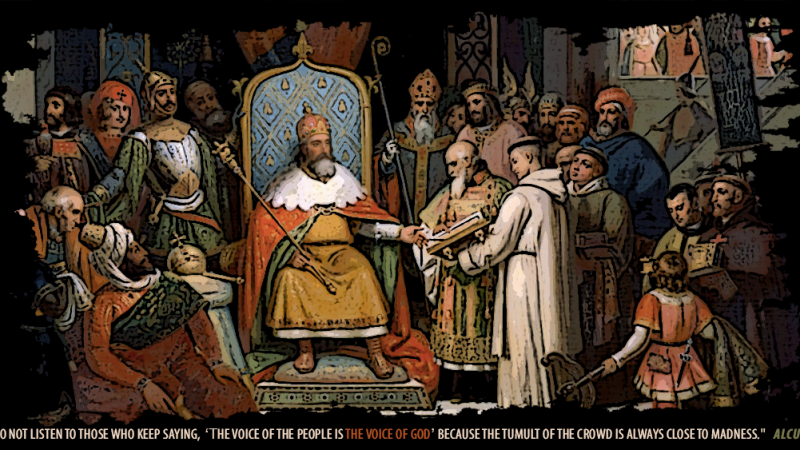

In 781, Charles met with an English monk and teacher from York named Alcuin. Charles painted a picture for him of a people who would grow in their love for God through the type of education Alcuin had himself experienced and then taught in York—a classical education that illiterate Charles wanted to experience himself.

Two hundred and fifty years earlier, St. Augustine had written about two cities, the City of Man and the City of God. Charles’ vision was to create a City of God throughout the entire Frankish empire through education. It was the type of vision not often seen in conquering monarchs, and Alcuin agreed to join Charles and take up residence at the royal court as Master of the Palace School.

Alcuin passionately began gathering all the documents he could to preserve the treasures and history of the past. In an age without printing presses, duplication could only be done by hand, written in books of vellum, so Alcuin brought together dozens of transcribers to painstakingly copy the great classics, filling libraries to educate the new empire thus beginning the Carolingian Renaissance. Alcuin established two schools, the “interior” school specifically for those headed into religious orders and the “exterior” school for the laity.

Aside from monastic discipline, the two schools were essentially the same. Both were built around teaching the seven liberal arts—grammar, rhetoric, logic (the trivium), geometry, arithmetic, music, and astronomy (the quadrivium). While the seven liberal arts were no new invention, Alcuin personally developed a formal curriculum on grammar, rhetoric, and dialectics and established classes by subject, taught by individual teachers.

It was the birth of a literary and artistic revival in Europe.

But why does this matter?

At some level, we all care about impacting future generations and leaving a legacy. Too often, we feel the pressure of the world, causing us to wonder why we are not the ones visible in the forefront, winning battles or conquering kingdoms. However, the reality is that true victory often comes through weakness, faithfulness, and dedication. It was the painstaking work of the scribes copying the texts that preserved them for centuries to come; it was Alcuin’s dedication to raising an educated people that produced a Christian empire. In the same way, today (as in every age) it is the love and care of a parent for a child which prepares the next generation to change the culture.

On Christmas day in 800 AD, Charles was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III and would forever become known as Charlemagne, “Charles the Great.” But it was Alcuin who had given Charlemagne the education necessary to provide a bedrock for the Carolingian Renaissance and, more importantly, Christendom for the next millennia.

Alcuin was an archetype of faithfulness in classical and Christian education, which resulted in a legacy that likely surpassed his wildest dreams. While he was not the most significant philosopher or original thinker, Alcuin was a dedicated teacher who helped bring about tremendous social revolution through education. His students were trained to contribute to the developing culture and began the establishment of what he saw as a true Imperium Christianum. He proved himself true to his motto, disce ut doceas (learn in order to teach) and remained known for his virtue and humility.

This story matters because the work of Charlemagne and Alcuin is just as significant to our day as it was to theirs because their story highlights something which has sometimes been called the “nobility of the commonplace.” This is the idea that the day-to-day investment of sacrificial faithfulness, which often seems insignificant at the moment, is that which truly brings about change in the world. Alcuin understood that battles could be won by the sword, but true victory is won through the education of the mind. He also recognized the need to invest in the education of his generation, not just for its own sake, but because it was the first step to spreading the gospel and building a City of God throughout Europe.