Classical Education, Then and Now (Part 2)

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Listen on Spotify

Do you ever find your children asking things like “Why do we go to this church?” or “Why do we follow that tradition?” What do we say when it seems like some of the things we do are considered “outdated” by the world’s standards?

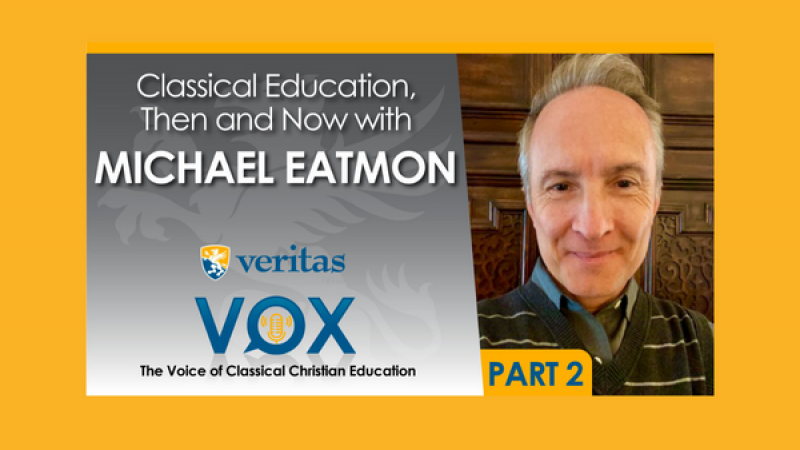

Join Veritas’ Director of Curriculum Development, Michael Eatmon, as we explore these questions and more! You will also get an exclusive preview of Veritas Press’ upcoming logic series as we discuss whether learning logic can help us cultivate a love of God.

This is part of a 3-episode series. Tap here to listen to Part 1 or tap here to listen to part 3.

Episode Transcription

Note: This transcription may vary from the words used in the original episode.

Marlin Detweiler:

Hello again! This is Marlin Detweiler. Laurie, my wife, is with me. We have as our guest for a second session Michael Eatmon who serves as our Director of Curriculum Development here at Veritas. Michael is the founding and original teacher at the Geneva School for School Year, starting in Orlando. And in the first session, we covered a little bit of that.

But today, we're going to continue on the conversation. There was a question you were partway through in our last session, and I'll repeat that and the follow-up question to it so that you can answer both of them in a way that kind of combines them because they are obviously related, as you'll see.

How should the church relate to and be involved in education is the first question. The second question is, how does the recent evolution of worship styles affect educational initiatives?

Michael Eatmon:

Excellent. Thank you for that. So as I mentioned in the previous session, but by way of a summary here, from my perspective, I think for most of the last 2000 years, the church has seen a great value in breathing its soul into the next generation. The Church has seen a great value in not only capturing what it believes to be true, good, and beautiful about the special revelation of God in the Scriptures and the general revelation of God in the world around us and within us.

The Church has valued passing on what it has viewed to be true, good, and beautiful to the next generation in order that these valuable things not be lost.

And I think within the last few generations, especially, although there have always been pockets of this here and there. But I think in the West, within the last few generations, there has been a greater attention paid to the experience of the individual. The experience of Christians gathered together in community in the here and now with perhaps– coupled with perhaps a depreciation of all that we have inherited from the past, even though it was Henry Ford who said that history is bunk. I think that there is that kind of sentiment, maybe among some church leaders today, that it doesn't really matter to us anymore what it is that the church used to do or Christians used to believe or Christian parents, how they used to instruct and raise their children in the church and the admonition in the Lord. The only thing that matters to us today is whether we love Jesus, whether we feel as if we have a vibrant relationship toward God and toward our neighbor.

And the first thing that I want to say about that is I agree that it is important for us to have a vibrant relationship with God. That it is important for us to desire to love and serve God and love and serve our neighbor. It's important for us to live in the here and now and not continually either be nostalgic for a golden age that never existed in the past, or pining away for some future that may or may not happen. So I think there's some truth in what's being communicated today when too many in Christian leadership in churches tend to devalue education.

But a lot is lost. And what is lost is what we talked about in our last session, actually about one of the best reasons to study classical languages, and that is because some of the greatest ideas that have ever been communicated were captured in these ancient languages, these ancient cultures, and ancient scriptures. Chief among them, of course, being the Bible.

So as I think about Christian education today, certainly, it's important for us to encourage and challenge and support Christian parents to raise their children in the nurture and the admonition of the Lord. That's always been important. It was important in Deuteronomy. It's important today, but I think it's more important today, even because so many Christians aren't getting the continual encouragement and reminder and challenge and support from their own church leadership.

And so that's where I think the work of Veritas and other Christian and classical publishers is so helpful not only to equip parents to take their God-given calling seriously, but also to equip them to bring up their children in such a way. Not only that they love Jesus, that they love and serve God, but that they love and serve neighbor.

And not only that, they are knowledgeable about the Scriptures and the God who is revealed therein but also, frankly, are knowledgeable about the world God has made about people outside themselves, about the life even within them. So God has called us to love Him with all of our heart, soul, mind, and strength. If we leave our mind out of the equation, we're not loving God as He has called us to.

And there's more to loving God with our mind than simply learning about the Bible and Christian history, however important they are, and they are. So I think because our contemporary culture really does focus a great deal on the here and now on individual experience and the experience of the gathered community and depreciates or devaluates that which has gone before, we run the risk of losing that which has gone before, unless we set out to recover not only lost tools of learning, but recapture the lost treasures of truth, goodness, and beauty that the past has handed down to us.

Marlin Detweiler:

Michael, before I ask a follow-up question on that, I want to ask a question about something that you said to make sure that it doesn't create something that's not understood. You mentioned the term ancient scriptures and then chief among them being the Bible. What do you mean then by ancient scriptures? If it's something more than the Bible.

Michael Eatmon:

I don't mean anything more than the Bible. I only mean ancient things that are written down.

Marlin Detweiler:

Okay. Thank you. I didn't want people to start thinking that at Veritas you, Laurie, I, or anyone else was thinking that scriptures and Bible were substantially synonymous.

Michael Eatmon:

Right!

Marlin Detweiler:

Well, we have a real evolution today, a real growing of contemporary, what we call sometimes seeker-sensitive worship, and candidly, it has not been a hotbed for the growth of classical Christian education. You've addressed that a little bit indirectly. Can you do that a little bit more directly? Tell me why you think that is.

Michael Eatmon:

Myself, I don't have all that much experience with contemporary seeker-sensitive worship. So I can't speak from the vantage point of someone who has experienced a great deal of it. But I think at least one aspect of the contemporary culture that we see in a seeker-sensitive church that tends to devalue education, at least from my perspective, is that it also tends to devalue the life of the mind, I think.

And I believe that we see in some of the worship styles, whether musically considered or lyrically considered. I think sometimes we see that there's a great appeal to the heart, and I'll use that in a contemporary sense of the term, a great appeal to the emotions to stir us, to feel good about our experience, to feel good about our relationship to God and one another.

But I think too often, contemporary worship expressions can sidestep either the education of the mind or the nourishing of the mind. And we need to take a look at it in a great place to see it starkly is to compare a set of lyrics from a contemporary worship chorus. And I say this as someone who appreciates, who can appreciate contemporary worship choruses, and I understand and appreciate how it can stir our emotions toward God and one another, which is a good thing. But if we said these lyrics, let's say, over against the richness, the theological richness, the linguistic richness, the cultural richness of what we find in, say, a traditional hymnal, I think we see that there is, again, a devaluing or at the very least a non- appreciation of the past for what it's handed down to us. And I think we see that there has been a loss in some of the richness of the theological, not only biblical-theological, but practical theological context that's captured organically, traditional worship of worship, traditional words in traditional hymns, traditional instruments.

This is not an apologetic, by the way, for everyone, everywhere, worshiping from a traditional hymnal with a pipe organ. It's simply to say that I think sometimes we force ourselves into an either-or, a false dichotomy scenario. So when the answer, the best answer is something that looks more like a golden mean between the extremes, where there there is a kind of correction that was necessary in Christian culture over the last couple of generations, where for so many people, Christian experience was all about just head knowledge and singing these beautiful hymns and having the right instruments and doing everything the way it's been done for centuries.

There was a kind of reaction to that to say, Yeah, but where's your heart? Are you stirred with joy and gratitude and Thanksgiving and praise toward God, and a desire to love and serve others by these things? And I think often the answer was no.

Marlin Detweiler:

That’s a very good point, I think. In the experience that Laurie and I have had in recent years, having been for a time a part of a seeker-sensitive church, we learned some things that we didn't learn from our experiences in reformed churches, chiefly the idea of really loving the lost. The reformed faith today is not a place, in our experience, where we learn that in the same way that we did there.

Laurie may have some further comment on that if you if you want to, Laurie, please do. And then, if you would move us into asking Michael about what he's working on currently and give him some softball questions to go there.

Laurie Detweiler:

Well, I would say that Michael and I have had this conversation; I see some of the same problems and what you call the tradition in the church that I do and what we're calling the Seeker Church. Right? And what I mean by that is how many churches are there today? All you have to do is drive around where most people live and see door after door that are shut or dwindling congregations. And I would say that in some senses a lot of the problem is the same, and that is, you know, 30 years– got to go further than that. 80 years ago, most children were taught the Bible, even if it was just because it was a moral story, they knew the essence of scripture. You know, my 93-year-old father is gone now. But it wasn't that long ago that I would have these conversations with him and said, you know, “We learned the basics of the Bible in public school.”

And so what I see happening today to churches, and unfortunately, I would say in the pastorate, is they've lost. They don't understand their worship. They don't understand the building that they're in and the symbolism and the meaning behind it. And they don't understand the liturgical calendar. And so if you don't have education behind all of that, what you end up with is this empty tomb, so to speak.

And so what happens in the seeker church then is they have the answer for the empty tomb. But education is still the problem on both sides of this. If you're educated, you get the heart because you want to love Jesus. Because if you read the Ancients and you read Augustine, you saw his deep love for Jesus, right? But if it's just words that you're going through in a liturgical service every week, it loses all of that. And so to me, the issue’s the same. It's just coming from, you know, one's dead, and the other is missing the component of the deep richness of history. Comment on that, Michael, because you say a lot better than I do!

Michael Eatmon:

No, no, I couldn't agree more. I think you're right. I think that going back, you said 80 years. I think that's a great spot as any– going back 80 years, and I can imagine, you know, extending the metaphor of the kids sitting around the table with dad, sort of in the book of Deuteronomy, they're asking about the Passover. We're like, “Dad, why are we doing this? Why are we going through the things we're going? Why do we say the things we do in church? Why does the church look like that? Why does the…” and dads are “I don't know.” And you're right, it's a problem.

And, you know, when we think about it, I want be careful not to commit what's called the etymological fallacy. But there is something to be said for the origin of the word education, which means “to lead out of”. You know, I think if we find ourselves as Christians, whether in a more traditional community or in a more contemporary community, if we find ourselves really walking in darkness. Either we've got an empty tomb, and sort of we've no idea what to say about that story, or we know that Jesus was in that empty tomb, but we don't know very much more about Jesus because we have that the answer is the same in both cases, and that is to be led out of the ignorance of our let out, the darkness of our ignorance and unbelief into the light of our truth and faith.

Laurie Detweiler:

And so I’m going to bring something in here. You're working on a project now that helps lead people out of that darkness, so to speak, right? It helps– I don't care if it's kids or adults, whomever it is, learn to think. And that's a logic project. That's part of why we at Veritas deemed it so important. Talk about that and how you see it as so important. And part of the answer for helping to solve this issue we've been talking about.

Michael Eatmon:

Yeah, great. Thanks. I am super excited about the Logic Project, and it's not simply because it's still currently on my plate. I'm just super excited about this project.

Laurie Detweiler:

And that you’re the author. Lets say that too!

Michael Eatmon:

That helps the excitement too. So I am I'm grateful for the opportunity. I'm grateful not only for the opportunity to author a work like this, but I'm grateful for the opportunity to author a work like this in this discipline because I believe logic is or this the study of how to think and reason better. But I believe it is super critical when we asked this question about education because it all gets back to– you know, I can imagine a Jesus when he was asked about, you know, sort of teacher, what was the greatest commandment in the law, right? Love the Lord, your God with all of your heart and mind and strength, love your neighbor as yourself on these two commandments saying all along the prophets and I can just imagine, you know, one of the little unnamed disciples in the back of the room sort of jumping up and saying, “How do we love God with all of our mind? How do we do that? I mean, maybe some of this other stuff I get, but that's really tripping me up.”

And I think a study of logic, a study of how to think and reason better, is a step we can take not only a step but the beginning of a lifelong journey that we engage in learning how ever more deeply and richly learning how to love God and others with all of our mind.

And this series that we're working on, I'd say, is different from other materials out there. And maybe I–yeah, let me say a little bit about that. And that is when Veritas sets out to bring a new material to bear in the marketplace; the first question that it asks is, “Can we can we invent a better mousetrap?”

I mean, there are already text materials and resources available out there. Are we just throwing another one in the heap or is or is there some way that we can offer something that we believe to be even better suited to meet certain needs that we see than what is available? And do we believe that we can do it in such a way that's consistent with our Christian commitment and our classical pedagogical views?

And the answer, I believe, to both of these questions with respect to logic was yes. So the current logic text that's being developed is book one in a two-book series. And even though we say book one, it actually has three parts to it. So it has a core content part. It has a student workbook part in which the students will be asked to apply and extend what they're learning in the chapters. And of course, it will have a teacher edition to it.

But what I'm most excited about– none of that makes for the better mousetrap necessarily. What I'm really excited about is what it addresses, what it covers, and how it does it. So first, what it addresses in many a logic one-course teachers teach their students a handful or two handfuls worth of what are called informal logical fallacies, and maybe they'll teach them the basics of what's called categorical logic.

So Aristotle's Square of Opposition in themes and variations on that topic, but they don't— many logic one courses don't do much more than that if even that, and for me, I taught logic for a number of years. I've taught teachers how to teach logic for a number of years. And for me, there are other not only important but crucial elements that should be involved in a first year in logic.

Number one, I think all studies in logic need to begin with an exploration of what it means to know something and, even more deeply, what it means to know the truth. Because all of the logic is kind of built on this assumption that, well, we're helping people think better so that they can get to the truth. Yeah, but that assumes certain things about knowledge and what truth is that I think sometimes go unsaid and unexplored in logic curricula.

So the first quarter or so of this book explores what's traditionally called “epistemology”, but we're not going to tell the kids that. It explores epistemology. It explores the foundation for why we believe certain things to be true, how we can claim to know things, what constitutes knowledge, and what do we mean when we're talking about truth.

The second quarter in this text turns to, unfortunately, a topic that's often completely disregarded in many courses on thinking and reasoning. And that is the field of cognitive biases. And the reason why it's understandable why it's ignored. And that is because it really wasn't part of the classical canon in teaching logic, in large part, again, because researching cognitive biases is from psychologists, neuroscientists, and others is a recent field, fairly recent field, even though certainly there were some hints at it in years, even centuries past, it really has come into its own in the last 40 to 50 years.

And cognitive biases different from logical fallacies is a logical fallacy is a kind of error in reasoning, whereas a cognitive bias is a is kind of short circuit in our brain's process of information. It's like you can't even get to the reasoning phase if you've had a short circuit in your information. And so the second quarter of the text addresses these cognitive biases.

The third quarter addresses logical fallacies. Now the logical fallacy section, we address some of the typical logical fallacies that one might find elsewhere. But one thing we do encourage in this section that may be different from some others, and I do it throughout the text, that is, it's not only important to me to teach students the foundational concepts and skills of how to think and reason better. That's important to me. But equally important is developing the character of the young logician. And we did the same thing when we developed the rhetoric series. So in A Rhetoric of Love, both books 1 and 2, of course, we were concerned with communicating core concepts and skills in the discipline of rhetoric, but we also wanted to develop help develop virtuous rhetoricians.

And so the same thing is true here in the logic text. So, for example, in the logical fallacies quarter, one of the things that we do is not only point out what these different logical fallacies are but show just how prone we ourselves are– the students who are learning it to committing them, also cautioning them against being logical fallacy police, even though they will do it anyway. And sit around the dining room table and write their parent's tickets for committing logical fallacies. So there's this third quarter that focuses on logical fallacies.

And then, the fourth introduces argumentation to the students. So argument is something that is typically covered in a thinking or reasoning course wherever a school teaches logic, but oftentimes it's only treated somewhat accidentally or incidentally in year one. And the real focus is in year two. And here, I wanted to make sure that we got a good, solid introduction to what constitutes not only the construction of a good argument but also give the students good handles to hold on to when evaluating others' arguments, not only when they're evaluating them from a logical perspective, but then also how they interact with people who come to different conclusions from what they do. So how to respond to dissenting voices.

That raises– that's content. That raises the other side of the coin. And that is the tone, approach, and style of this text. And I hope it's a better mousetrap. I believe that it is. And that is I want for the student reading this and the teacher, too, frankly, I don't want for them to feel as though they have to endure logic.

Laurie Detweiler:

Or that it’s crammed down their throat like there's a Bible verse on every page.

Michael Eatmon:

I don't want any sort of a force-feeding experience. I want them to enjoy it, to find joy in it, to find delight in it. And so there are some elements about it, I think, that will help that happen. One of them is there are various character narrative arcs that are woven throughout the text, and I won't go into too much detail, but that the two lead characters are these two middle school boys. And I feel that as anyone is reading this text, you can say, “Okay, well, I'm not Renny, this character, but I know some Rennys in my life, or I went to school with some Rennys. And Renny and his best friend, and Renny’s sister and some of her classmates in college, Renny and his best friend, Jose's logic teacher, and her mother-in-law. They have these ongoing, I think, engaging, colorful conversations that don't only illustrate different cognitive biases and problems with epistemology and logical fallacies. They're not simply an illustrative tool, but they're also a tool to help engage the students in thoughtful reflection on the development of the character of the young logician.

And so I hope somewhat inductive learning through the back door. I hope that they will grow as much through connecting with these characters and growing with these characters as they learn even from the more direct instruction in the chapters.

Marlin Detweiler:

Michael, we should be mindful of our listener's time and what that means is two things. One, we will do a third session and talk about rhetoric, a project that you recently completed, but also if you could give us a minute of what Book 2 will look like. As you mentioned, logic is to books two years. You've talked a lot about logic 1. Obviously, that's because it's very current for you. But I know you have some designs on Logic2 as well. Tell us about it.

Michael Eatmon:

Sure, sure. So in Logic 2, I want to continue the same kind of tone, approach, and style that I did in book one. Don't want it to be an endurance, but an enjoyment. But in terms of the difference in the content book 1 focuses on informal logic. Informal logic is the logic of everyday, ordinary natural conversation.

Book 2 will focus on formal logic. Formal logic is a method whereby we can abstract ideas from normal natural conversation, reduce them into a kind of symbolic language, and then analyze them, look at them for their validity. So look at them for just how logical or not that they are.

Logic 1 tends to focus on two kinds of reasoning called inductive and abductive reasoning, and book 2 will focus on deductive reasoning, which is the reasoning that many people would associate say with Aristotle and the Aristotelian tradition.

Marlin Detweiler:

Thank you. We are Veritas Vox, the voice of classical Christian education. Today we've been talking to Michael Eatmon: in a second session where he followed up on some questions that were dangling from the first session about the church and its connection to education and then got a chance to hear a little bit more about his work in the project of creating the Veritas Logic curriculum.

He recently worked on helping to create two years of rhetoric curriculum, and in a third session we will talk to him about that. You won't want to miss it because it's in that that you will hear some response to our first guest at Veritas Vox in Sessions one and two with Doug Wilson who, as many of you know, has a rhetorical approach sometimes that embraces a pretty bold approach of satire and other sometimes strong rhetorical skills that Michael has some opinions about, too. Thank you, Michael. We are Veritas Vox, the voice of classical Christian education. Thanks for joining us.