Tour of Omnibus Series, Part 2: History, Herodotus, Thucydides, & Tuchman

Historians are terrible at the board game Risk, or that is what a history professor once told me. Historians know that you should never invade Russia. Of course, in Risk, which recapitulates a world war challenging players to dominate all other opponents, invading Russia is sometimes the right move.

Henry Ford famously said, “History is bunk!"

So if history teaches us to be bad at certain board games and is criticized by the geniuses, why do we spend so much time in Omnibus reading History?

This post is the second post in a series that I am calling the Tour of Omnibus which explains why we read all of the different types of books that we read in Omnibus. My earlier post on Epic Poetry can be found at Tour of Omnibus, Part 1.

So, why do we read history?

- History helps us know ourselves

We are not disembodied spirits. We are spirits connected to bodies that live in place and time. One of the largest crises of modern humans is the crisis of identity. It is a crisis because we have placed the entire weight of identity onto the individual rather than instructing the individual to look to nature, religion, and history to define some really important parts of our identity.

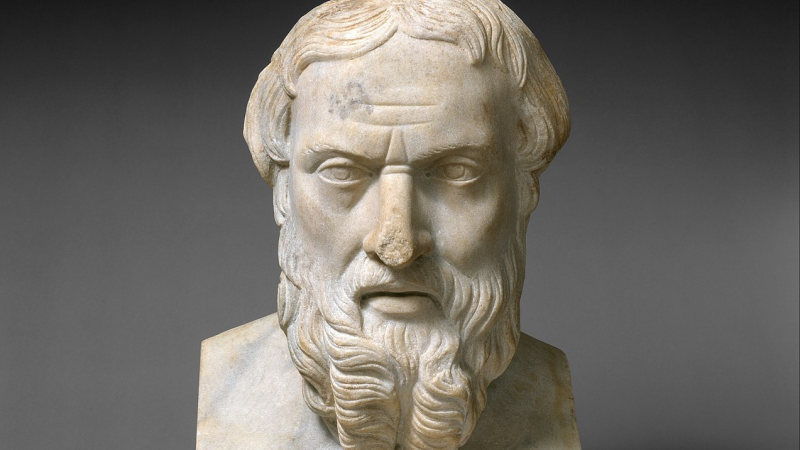

History helps us discover our identity because it connects us to the stories of the past. Some of these stories might involve your direct ancestors. Supposedly I have an ancestor that was part of the Union Army who almost starved to death in Andersonville Prison during the Civil War. That story, if it is true, tells me something about my family, but some of the most important stories concerning our identity actually connect to ideas or broader connections that we hold to. I was born into Western Civilization. I better understand what it means to be part of Greco-Roman civilization by reading Herodotus and seeing the courage that it took to stand against the Persian armies under Xerxes on the beaches of Marathon or at the pass at Thermopylae. Were the outcomes of this war changed, it is unlikely that ideas like democracy and classical education would have ever made it to us today.

Because of books like Herodotus we can know ourselves and our own lives better.

2. History helps us understand our place and why the world works as it does

Why has there been continual trouble in the Middle East between Arabs and Israelis? One could trace the problems back to Abraham, but the issues go deeper and they are more snarled in the modern age. We can find out about this by reading books like Barbara Tuchman’s Guns of August. In this amazing history book which chronicles the first month of the First World War. We learn that the countries of Western Europe all knew that war was coming. In the Mediterranean, the British Navy was tracking the German Battlecruiser Goeben. That German boat eventually docks in the harbor of Istanbul in the Ottoman Empire. This drew the Ottoman Empire into the War on the side of the Axis powers. This means that they were eventually on the losing side and the Western powers, the victors, divided up the Ottoman Empire and set in motion the tension and bloodshed that eventually led to the founding of the modern nation of Israel in 1948. Amazingly, the two-year old Tuchman was actually an “eyewitness” of this chapter of history because her family was on a boat near Istanbul when the War was declared and the British and German ships exchanged fire.

The best of history illuminates the present as much as it clarifies the past. It helps you understand why the world works the way it does.

3. History brings us into the presence of greatness and helps us make judgment about the happenings and people of our day

A few years ago, I read the “best” biography of each American President from Washington to Clinton. It was an interesting and helpful project. Each time a President leaves office, historians start rating them. Are they best, worst, or somewhere in between? Sometimes these historians are influenced by politics and by the fallacy that C. S. Lewis termed “chronological snobbery” which wrongly asserts that the leaders and ideas of our day are best simply because they are newest.

Reading history helps us make judgments about our own days. Is our current President the greatest leader in history? Listening to the Funeral Oration of Pericles in the pages of The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides helps us see what real rhetorical greatness looks like. These sorts of books help us know the difference between Jimmy Carter, JFK, and Winston Churchill.

Also, history helps us see how principles work themselves out in politics. One of my favorite examples of this is Thucydides’s recollecting of the revolution that crept into the city of Corcyra as Athens and Sparta struggled to control the entire Greek world. Here is a snippet:

So bloody was the march of the revolution, and the impression which it made was the greater as it was one of the first to occur. ...Revolution thus ran its course from city to city, and the places which it arrived at last, from having heard what had been done before, carried to a still greater excess the refinement of their inventions, as manifested in the cunning of their enterprises and the atrocity of their reprisals. Words had to change their ordinary meaning and to take that which was now given them. Reckless audacity came to be considered the courage of a loyal ally; prudent hesitation, specious cowardice; moderation was held to be a cloak for unmanliness; ability to see all sides of a question, inaptness to act on any. Frantic violence became the attribute of manliness; cautious plotting, a justifiable means of self-defence. The advocate of extreme measures was always trustworthy; his opponent a man to be suspected. To succeed in a plot was to have a shrewd head, to divine a plot a still shrewder; but to try to provide against having to do either was to break up your party and to be afraid of your adversaries... (From The Peloponnesian War, Part III, 69-85).

You might see shadows on this sort of creep toward revolution in modern American politics. Studying history doesn’t mean that we can know what is going to happen next, but it does show us where certain trends lead.

4. Finally, history humbles us and helps us see that hand of God’s providence

So often in history, the little things matter. In The Guns of August, the German General von Kluck was supposed to envelope Paris in a motion that brought the strong right divisions of the German army to curl around and surround the French capital. He turned too early, however. This one mistake probably caused, in a very real way, the destruction of the great powers of Western Europe, inaugurated the nightmare of trench warfare, set in motion the rise of the power of the United States, and the eventual rise of Adolf Hitler. All of this caused because of the massive arrogance of the West and one simple mistake.

The countries of the West, of course, had over the 150 years before World War I walked away from God, from orthodox Christianity, and had developed such arrogance that they couldn’t see that they were walking off a cliff. Pride goes before the fall. It also precedes the battle of the Somme where 1,000,000 men died. This war also formed the imagination of Lewis and Tolkien who both fought and were injured rather than killed as so many were.

We read history to know ourselves, our world, and God’s providence. It helps us make wise judgments and saves us from narrow thinking. Reading history in Omnibus is one of the most important types of reading in the entire program.