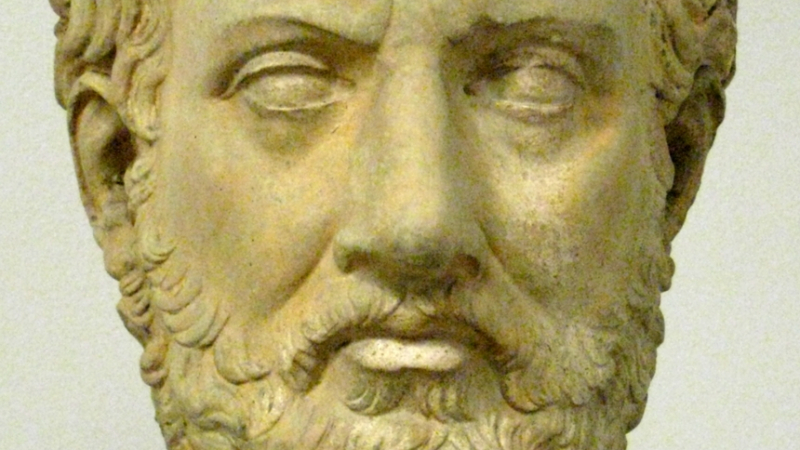

History as a Key to Current Events: The Case Study of Corcyra (Thucydides)

History is a great source of wisdom, but too often we do not heed what it saying to us. Sometimes history gives warnings; other times it provides solace. In some cases, it shows you the cliff and gives you an opportunity to avoiding falling off it.

Recently, I have noticed that one of the stories of Thucydides' Peloponnesian War keeps echoing in my mind: the story of the Revolution in Corcyra. American culture is currently experiencing a time of deep division.

Here is a summary of the backstory of Corcyra. The Peloponnesian War was fought between Athens and her allies and Sparta and her allies. These two City-States were leaders of two “parties” or leagues. They were sort of like Republicans and Democrats but much more war-like. The Greeks did not have an overarching country like the United States nor did they live in an empire, although Athens and their Delian League were looking increasingly like an empire. Instead, the Greeks lived in City-States, independent cities that made their own decisions about life, law, and alliances. During the Peloponnesian War, emissaries from Athens and Sparta would try to get other cities to align with their party. Often, political leaders in cities were convinced, threatened, or bribed to use their influence to draw their city into alliance. Sometimes this would end in deep divisions within a city. Corcyra was one of these cities. Some leaders aligned with Athens and others wanted to back Sparta. Here is a link to Thucydides' description of the Revolution in Corcyra. Here is a selection of some of the key passage (III.82):

So bloody was the march of the revolution, and the impression which it made was the greater as it was one of the first to occur. … In peace there would have been neither the pretext nor the wish to make such an invitation; but in war, with an alliance always at the command of either faction for the hurt of their adversaries and their own corresponding advantage, opportunities for bringing in the foreigner were never wanting to the revolutionary parties…. Revolution thus ran its course from city to city, and the places which it arrived at last, from having heard what had been done before, carried to a still greater excess the refinement of their inventions, as manifested in the cunning of their enterprises and the atrocity of their reprisals. Words had to change their ordinary meaning and to take that which was now given them. Reckless audacity came to be considered the courage of a loyal ally; prudent hesitation, specious cowardice; moderation was held to be a cloak for unmanliness; ability to see all sides of a question, inaptness to act on any. Frantic violence became the attribute of manliness; cautious plotting, a justifiable means of self-defence. The advocate of extreme measures was always trustworthy; his opponent a man to be suspected. To succeed in a plot was to have a shrewd head, to divine a plot a still shrewder; but to try to provide against having to do either was to break up your party and to be afraid of your adversaries. In fine (conclusion), to forestall an intending criminal, or to suggest the idea of a crime where it was wanting, was equally commended until even blood became a weaker tie than party, from the superior readiness of those united by the latter to dare everything without reserve; … Revenge also was held of more account than self-preservation. Oaths of reconciliation, being only proffered on either side to meet an immediate difficulty, only held good so long as no other weapon was at hand; but when opportunity offered, he who first ventured to seize it and to take his enemy off his guard, thought this perfidious vengeance sweeter than an open one, since, considerations of safety apart, success by treachery won him the palm of superior intelligence. Indeed it is generally the case that men are readier to call rogues clever than simpletons honest, and are as ashamed of being the second as they are proud of being the first. The cause of all these evils was the lust for power arising from greed and ambition; and from these passions proceeded the violence of parties once engaged in contention… (Selections from Book III.82).

This historical echo has caused me to reflect on ways history can be a useful tool as we study current events. To learn from history we must see patterns, principles, and precedent.

Be aware of the patterns of history.

Did you recognize anything in Thucydides that reminded you of our political division today? It really does remind me of the division I see in our culture. Consider these patterns:

- In times of division, people behave in ways that would never enter their minds during times of more unity.

- Words are often the first casualties during times of revolution. People change the meaning of words and they stop keeping their words.

- When trust breaks down, people scramble for power, often violently.

To profit from history we need to be aware of these patterns and recognize them when the recur.

Be aware of the principles of history.

We can also see the principles of history and learn from them. Patterns repeat; principles are timeless truths. In this description, we see a few principles of revolution that we should consider:

- Revolution, once started, is very difficult to contain. It leaks out and it “ran its course from city to city.” Some people play a revolution, but that sort of play is foolish because once violence starts it will go everywhere.

- Revolution is a learning process. Thucydides says, “the places which it arrived at last, from having heard what had been done before, carried to a still greater excess the refinement of their inventions, as manifested in the cunning of their enterprises and the atrocity of their reprisals.” It does not wind down; it winds up. People learn how to harm their enemies more effectively. Once a line of decorum, civility, or law has been crossed, the next offender goes even further. This concept is called “escalation” it happens in times of revolution and war whether those times occur in Ancient Greece, the Reign of Terror in Paris, or even in the Vietnam War.

- Revolution tears the ties of natural affection apart. Revolution makes party everything. It diminishes and even replaces the ties of commonwealth, religion, and family.

Finally, be aware of the precedence in history.

This is probably the most important lesson we can learn about revolution. It happens. It is hard to imagine that brother can be turned against brother or neighbor against neighbor, but throughout history, it happens. The means we must study it and do all that we can to avoid it. Sinful revolution is one of the most terrible sins, and reading history helps us recognize the beginnings of it, so that we can oppose it and, Lord willing, prevent it.